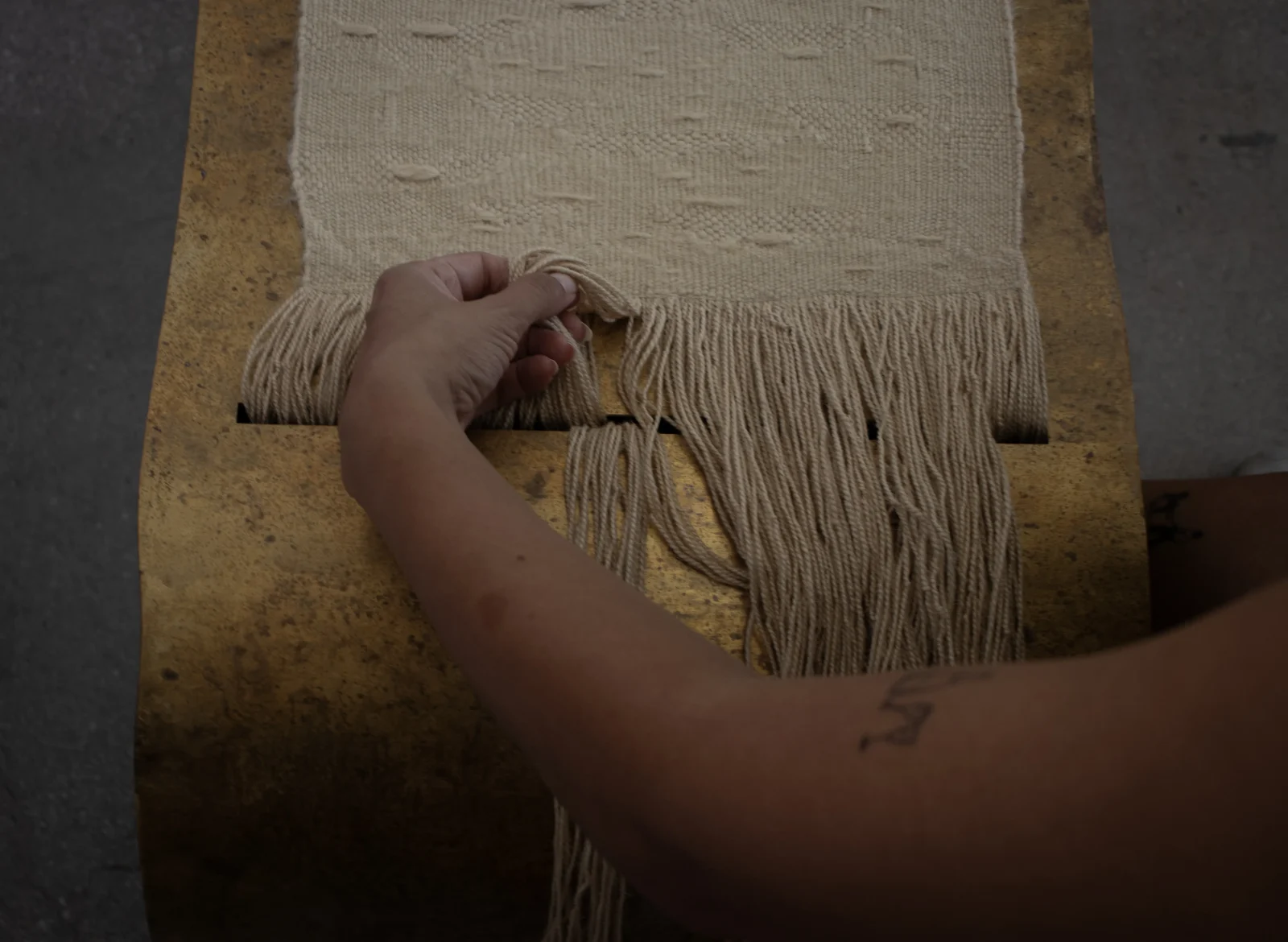

ADORNO Future50 2026: Authority of the Hand

Manual ability changes how a designer moves through every stage of making. The difference between a practiced hand and a new one often shows up in what is avoided as much as in what is done, in the decisions that are held back, redirected, or reconsidered before they become fixed in material. Years spent working with a tool build an understanding of its limits and its range, and that familiarity begins to guide decisions long before a piece takes final form.

For the Future50 designers gathered here, technical skill shapes the concept itself. Knowing how glass shifts under heat, how wood responds to pressure, or how clay moves while drying informs choices from the outset. The more time a maker spends working directly with their materials and tools, the more clearly they recognize when a piece feels complete and when it does not. Authority of the Hand refers to this accumulation of practiced knowledge. It points to designers who have spent enough time making to let experience guide their decisions, and who remain present where those decisions matter most. The works featured here reflect that depth of engagement, where the hand is not a signature but a source of understanding.

Buket Hoşcan Bazman – Izmir, Turkey

Buket Hoşcan Bazman works closely with brass, wood, and stone, treating each material as something to be learned from rather than imposed upon. She develops her pieces alongside skilled artisans, staying involved from first cut to final finish. In works like the Curio series, hand-formed brass, woven kilim, and porcelain come together through careful metalwork and tactile judgment. Her furniture shows how tradition and contemporary form meet through practiced, material-led making.

Ceren Gürkan – İstanbul, Turkey

Ceren Gürkan works directly with clay and glass, where control of heat, timing, and touch determines the final form. Her Asea wall pieces show how hand-shaped porcelain and hand-blown glass carry the record of each movement, from forming the waves to setting the light. The surfaces rely on practiced pressure and repetition, not molds or shortcuts, so each piece settles differently. Her work reflects a maker who understands material through handling it, and who lets that knowledge guide every decision.

Curtis Bloxsidge – Melbourne, Australia

Curtis Bloxsidge approaches jarrah through the habits of a cabinetmaker, reading grain, density, and tension before committing to a cut. His lamps and furniture come together through joinery, shaping, and fitting done by hand, where proportion is tested directly in timber. Long familiarity with the material allows him to work with restraint, letting weight, surface, and shadow carry the character of each piece.

Don Heston Studio – London, United Kingdom

Don Heston works as a self-taught maker who has learned wood through handling it, selecting boards for grain, color, and irregularity. His furniture brings together carving, shaping, and finishing that respond to what the timber reveals along the way. Rather than forcing uniformity, he relies on practiced judgment to decide when a surface, curve, or junction feels right in the hand and in the room.

Josh Page Studio – Kent, United Kingdom

Josh Page runs a small wood workshop where making begins with the slab in front of him and the tools he knows well. His sideboards, stools, and chairs are cut, carved, and assembled by hand, often adapting to the quirks of each board. Time spent framing and working wood has trained his eye to recognize proportion and balance through direct contact with the material.

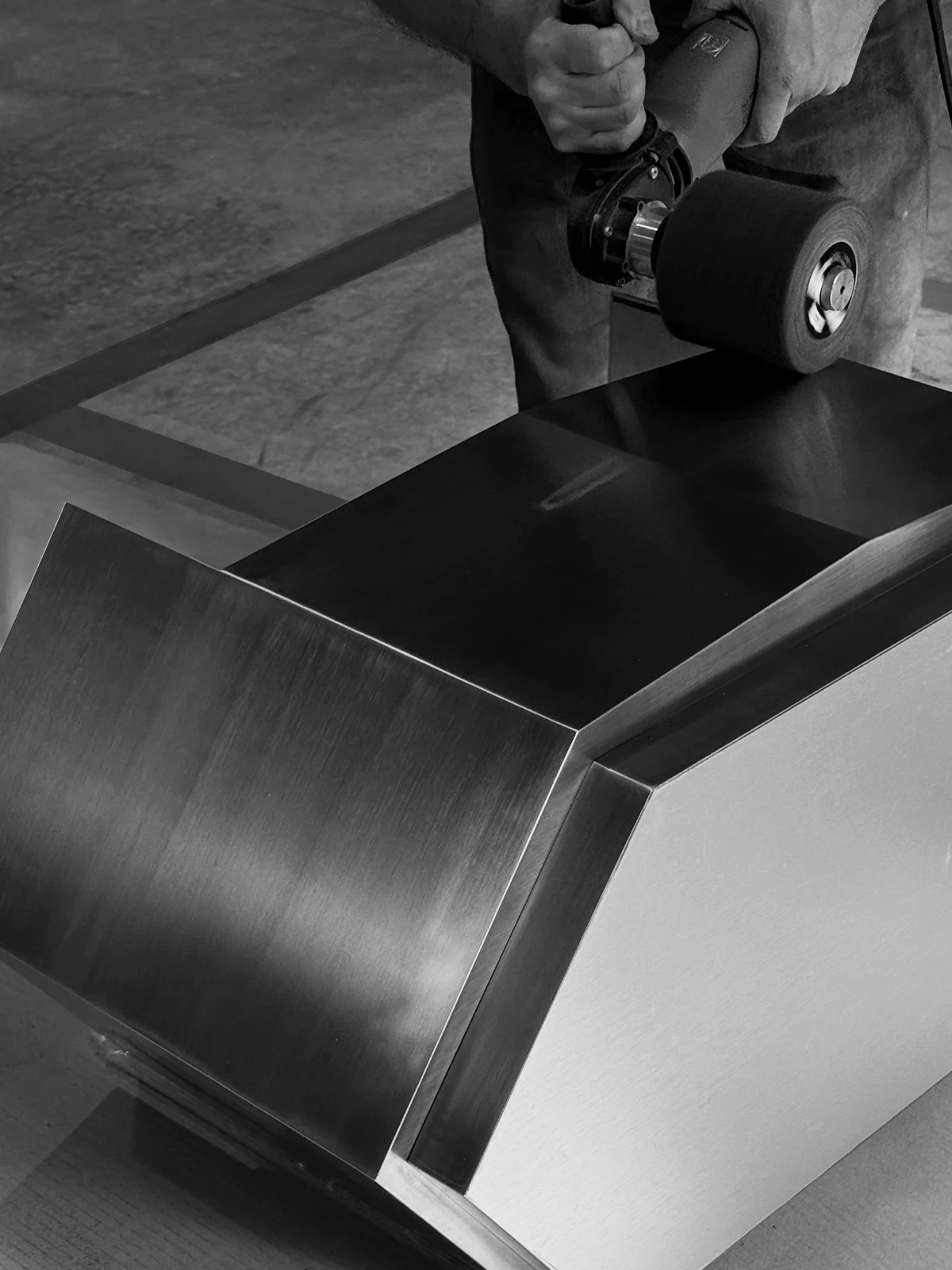

Maison Cédrat – Montpellier, France

Maison Cédrat builds its objects and lighting through Mediterranean craft knowledge in clay and paper, working with regional workshops in France. Alix and Pierre use drawing and hand studies to test forms before they move into production, keeping the hand active throughout development. In pieces like Nova and Écla, shaping, assembling, and finishing rely on practiced gestures that tie material, place, and authorship together.

MILA ZILA – Nový Bor, Czech Republic

MILA ZILA, by Ľudmila Žilková, works with molten glass in direct dialogue with heat, gravity, and timing, shaping each piece while the material is still in motion. Her PERSONA mirrors and glassware are blown, spun, and silvered by hand, where slight shifts in movement leave lasting layers and variations. Years at the furnace give her the judgment to sense when the material has reached its limit, allowing experience and touch to determine the final form.

POÉMIA – Lisbon, Portugal

POÉMIA, founded by Ricardo Costa, grows from a lineage of naval carpenters and a lifelong familiarity with wood. Working through stacked lamination and careful hand-sculpting, he bends and tensions timber into flowing light sculptures that hold their shape through precise control. Lamps like Pérola and Maré show how far wood can be pushed without losing its integrity. POÉMIA’s practice rests on repetition and feel, where form settles through the hand rather than being imposed on it.

Sophia Taillet – Paris, France

Sophia Taillet approaches furniture as a form of sculpture shaped through direct engagement with steel and glass. Trained in Paris and deepened through glassmaking residencies, she works through heating, bending, and testing material until form and structure align. Pieces like the Curve Table and STYX mirrors depend on close control of temperature, weight, and balance. Her authority comes from knowing how far glass and metal will go, and adjusting the work in response to what the material allows.

Studio Alexander Knysch – Waiblingen, Germany

Studio Alexander Knysch shapes furniture through direct, physical work with wood, clay, stone, and glass, where form is resolved by carving, cutting, and adjusting in the workshop. Proportion and balance are tested at full scale, with decisions made in front of the material rather than on a screen. His lamps and tables carry the traces of that process, from hand-shaped curves to individually formed clay elements. Each piece is worked through until weight, surface, and structure feel fully settled.

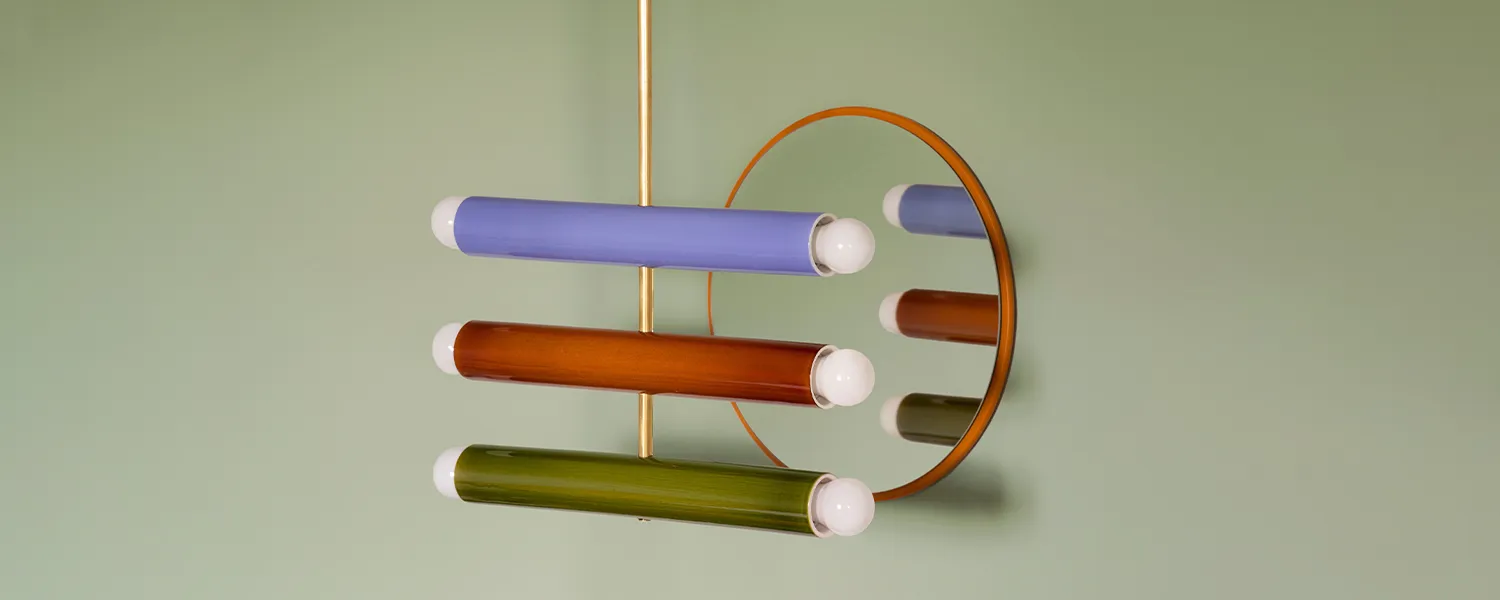

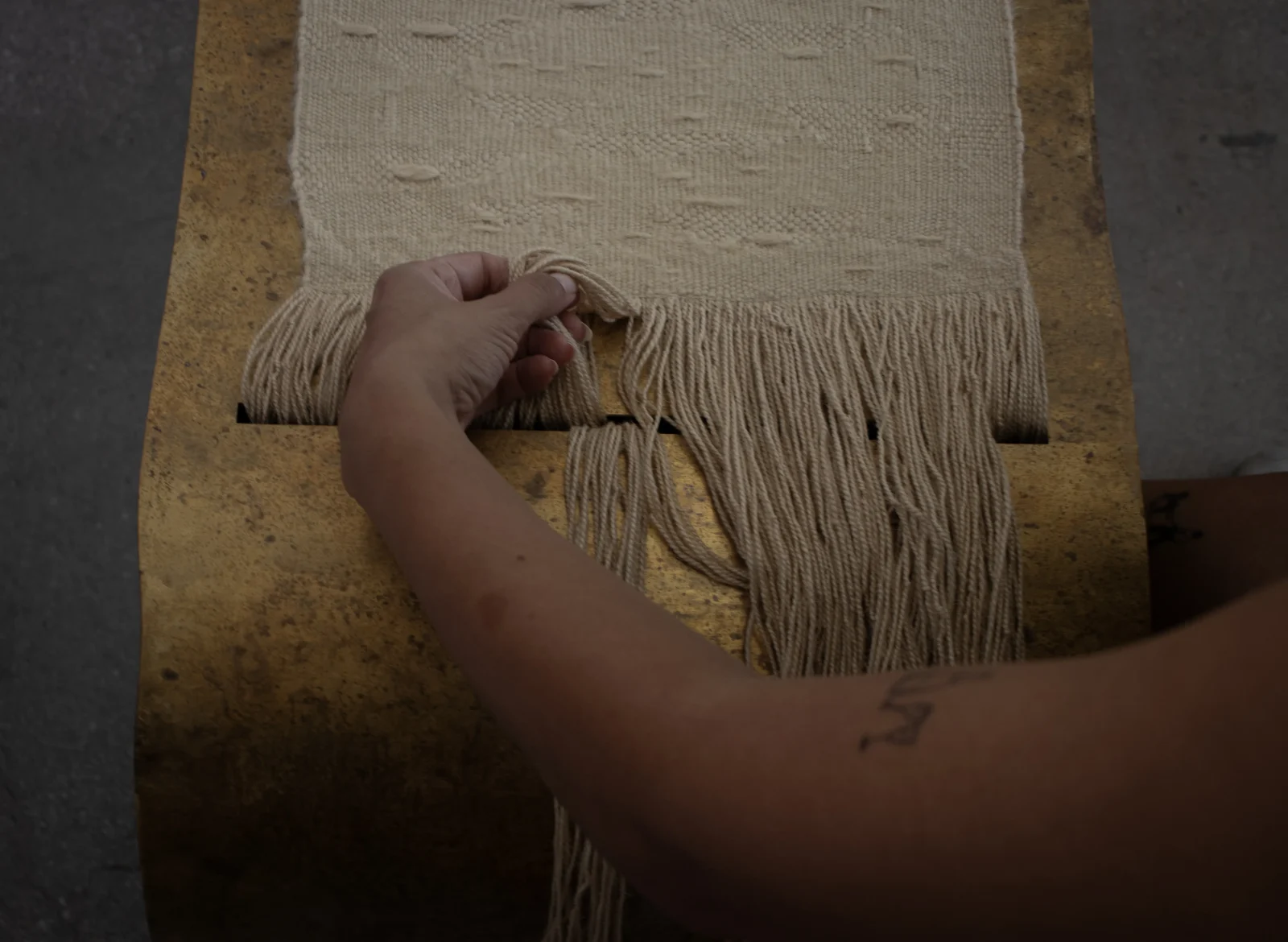

Studio Ēeme – Cascais, Portugal

Studio Ēeme works with clay as a responsive material, shaping each light and sculpture by hand from single slabs of stoneware. Founder Marie-Laure Davy draws on years of ceramic training and a physical practice rooted in movement, where gestures in the studio translate into folds, drapes, and curves in clay. The Folding and Unfolding sconces and Abundance pieces show how small shifts of pressure and timing alter light, shadow, and surface. Each form is guided through making until touch and experience signal that it is ready to be fired.

Vital Lainé – Plouër-sur-Rance, France

Vital Lainé works in close contact with wood, shaping each piece near the sawmill where his material is cut and sorted. Years of drawing, modeling, and carving give him the judgment to read grain, knots, and density as guides for proportion and structure. In works like the Avivé Chair and his cairn-inspired furniture, he preserves sawmill markings and natural irregularities, letting prior histories remain visible. His expertise appears in how he responds to what each board allows, using skill and restraint to settle the final form.

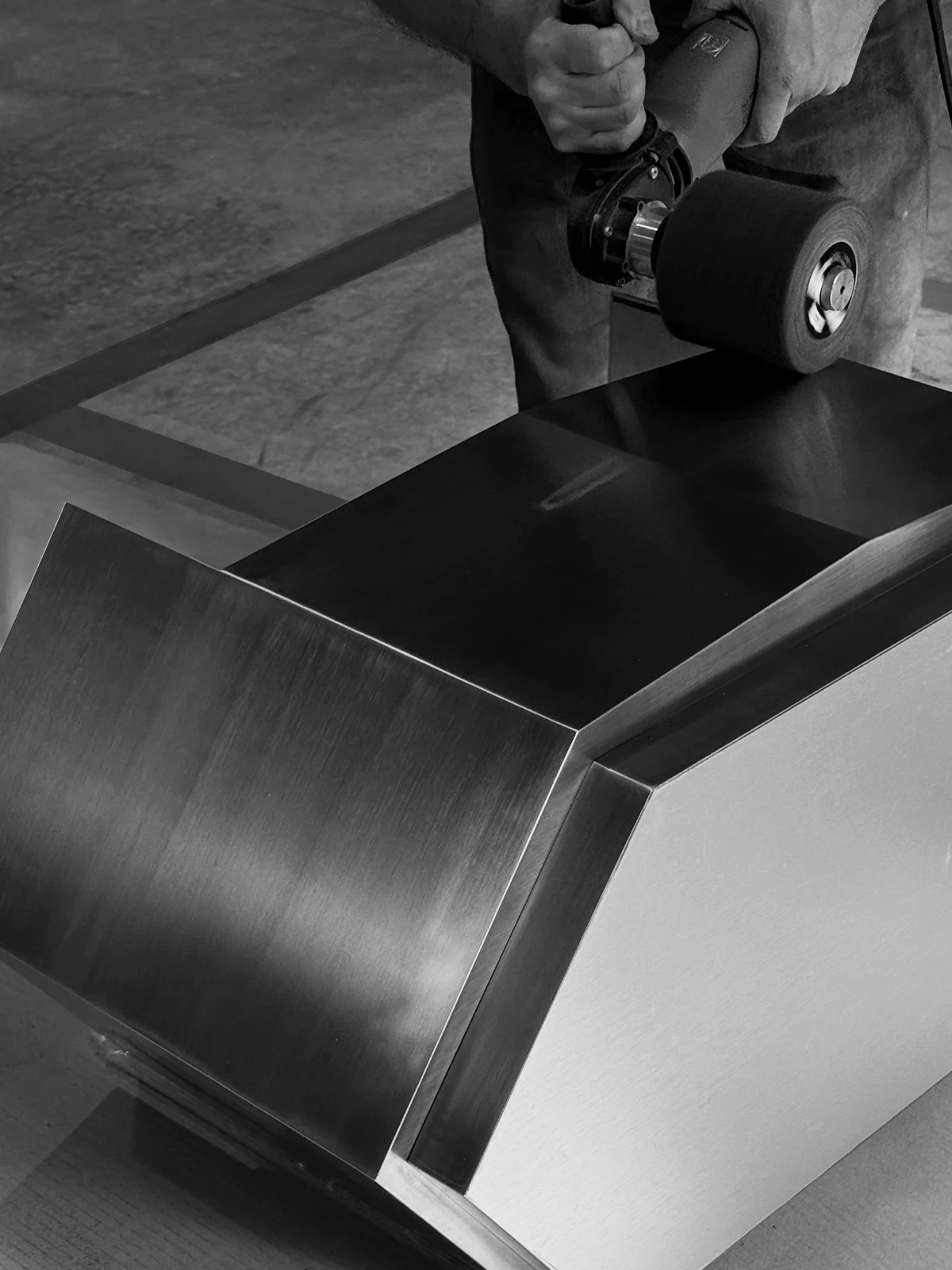

Zoé Wolker – Lisbon, Portugal

Zoé Wolker brings architectural training into furniture with the discipline of someone used to resolving real spaces. Years of practice sharpen her sense of proportion, alignment, and how light moves across a surface. In pieces like the PARAVENT screen and AME pedestals, small shifts in rhythm, perforation, and reflection are calibrated by hand and eye. Her work carries the confidence of long experience, where form, light, and structure are resolved through practiced judgment rather than effect.