‘The Brutalist’ Invites Interpretation: Finding Meaning in the Raw and Unspoken

When asked why he chose architecture as his career and passion, Adrien Brody’s character responds with a question: “Is there a better description of a cube than its construction?” These words, spoken by László Tóth in The Brutalist, encapsulate the philosophy of an architectural movement that is still today, both revered and reviled. Brutalism is confrontational, unadorned, and unapologetically honest—qualities that make it a perfect metaphor for Tóth’s journey as a Hungarian-Jewish architect and Holocaust survivor rebuilding his life in postwar America.

To fully appreciate the film’s exploration of resilience, survival, and creativity, it’s essential to understand the movement it draws its name from. Much like Tóth, who faces displacement, trauma, and prejudice, Brutalism emerges from a world irrevocably scarred by war, striving to create something enduring in the aftermath of destruction.

A Quick The Brutalist Primer : Origins of Brutalism

Brutalism emerged in the mid-20th century, born from the urgent need to rebuild cities quickly and efficiently. Rooted in the principles of Modernism, the movement was defined by raw materials—most notably béton brut (raw concrete)—and a rejection of unnecessary ornamentation. Brutalist architecture lays its construction bare, celebrating the functionality and form of its skeletal structures.

Pioneers such as Le Corbusier and Ernő Goldfinger—a Hungarian-born Jewish architect, much like the fictional László Tóth in The Brutalist—exemplified the style’s monumental yet utilitarian ideology. Goldfinger’s work, including London’s Trellick Tower, embodies Brutalism’s capacity to merge imposing forms with practical purpose. However, the style’s stark aesthetic and heavy reliance on concrete were divisive from the start. Prince Charles famously derided Brutalist buildings as “monstrous carbuncles,” and Goldfinger himself became a controversial figure. The pre-war demolition of Hampstead cottages to make way for his house at 2 Willow Road drew sharp criticism, including from neighbor Ian Fleming. Fleming’s disdain ran so deep that he named a Bond villain after the architect.

Despite its polarizing reception, Brutalism was never solely about appearances. It prioritized housing the masses, fostering communal spaces (exactly Tóth’s ambition in The Brutalist), and addressing the functional demands of a postwar world—charging the movement with a profound social conscience.

Elements of Brutalism

- Materials: Brutalism is most commonly associated with raw, unfinished concrete, though steel and brick are also used. Notably, marble appears in The Brutalist, used as both material and narrative device.

- Exposed Structure: Buildings often highlight structural elements like beams, columns, and supports, rather than hiding them.

- Geometric Forms: The style is characterized by large, angular, and bold shapes that make a strong visual impact.

- Textured Surfaces: Rough textures are a key feature, with concrete often retaining the imprints of wooden boards used during pouring.

- Modular Elements: Many Brutalist buildings use repetitive, modular components that create a sense of order and uniformity.

- Lack of Ornamentation: Decorative details are absent, focusing instead on raw materials and functionality.

What does Brutalism Actually Mean?

One of the greatest misunderstandings about Brutalism lies in its name. The term “Brutalism” doesn’t stem from the English word “brutal,” with its associations of harshness and cruelty, but from the French béton brut, meaning “raw concrete.” This reference to unadorned material, central to the movement, has been misinterpreted, leading many to equate the style with brutality, imposing structures, and even ugliness.

Brutalism remains polarizing. Its stark forms and lack of ornamentation are often seen as off-putting or ugly, which is fair enough. But this reaction – in part – stems from a linguistic misunderstanding that overshadows the style’s philosophy: prioritizing utility, functionality, and resilience in a world eager to rebuild. While opinions on its beauty will always vary, the notion that Brutalism is “brutal” because of its name deserves to be laid to rest.

In fact, the word “brutal” traces back to the Latin brūtus, meaning “dull,” “stupid,” or “insensitive.” Over centuries, it evolved to include associations with animalistic or coarse behavior, connoting a lack of refinement. By the time “brutal” entered English via Middle French in the late Middle Ages, it had acquired meanings like “harsh,” “cruel,” or “merciless.” Quite a far cry from the intent behind the architectural style.

This divergence from the French béton brut, lies at the heart of Brutalism’s linguistic confusion. Though subjective tastes will always vary, it’s undeniable that the English sense of “brutal” has unfairly shaped public perception of the architectural style, obscuring its intent to reflect resilience, purpose, and honesty in the aftermath of destruction.

A Cycle of Re-appreciation

Beyond linguistics, Brutalism, like the refugees and architects who helped shape it, has often been misunderstood and undervalued. For decades, these buildings were vilified as symbols of urban decay, their concrete facades seen as oppressive rather than inspiring. Yet as time passes, perspectives shift. Buildings like Boston City Hall, London’s Barbican Centre, and Montreal’s Habitat 67 are celebrated for their boldness and innovation. Critics who once dismissed them now recognize their sculptural power and historical significance. To be clear, there are still many who disdain Brutalism, including these very buildings—it is, after all, subjective. But whether negative or positive, Brutalism always elicits strong responses. It seems to touch a particularly visceral, human nerve.

This cyclical nature of design appreciation is central to Brutalism’s legacy. What was once shunned becomes revered, as new generations find meaning in what was previously overlooked. In this way, Brutalism reflects not only the resilience of its creators but also the evolving tastes and values of society.

Who – or what? – is The Brutalist?

What stands out about the film is how much remains ‘unsaid,’ leaving it up to the audience to interpret. Much like Brutalism itself, its appeal is in the eye of the beholder. The Brutalist encourages us to experience Brutalism for what it is, beyond words or definitions. As one critic put it when describing the film itself, “You can try to describe it, but nothing can match the power of simply opening your eyes”. The same could be said about Brutalism, and it echoes the question: “Is there a better definition of a cube than its construction?”

The story explores how art and architecture can be shaped by pain. Tóth, like Brutalism itself, is a product of trauma, yet he channels that pain into his work. His stark, functional designs mirror his struggle for survival and adaptation in a foreign land. The film asks a poignant question: Who—or what—is the titular “The Brutalist”? Is it Tóth, with his unyielding resolve? Is it his patron, wealthy industrialist Harrison Lee Van Buren? Is it more simply the architectural movement he embodies? Or is it the postwar world itself, grappling with its scars?

As one of the film’s creators noted in an interview, Brutalism is forward-looking. It captures the spirit of an era defined by the need to rebuild, but it also offers lessons for the present. Its raw honesty challenges us to confront the realities of our time, just as Tóth’s designs force his fictional clients to face theirs. In the end, The Brutalist isn’t just about architecture; it’s about resilience, adaptation, and the beauty of starting over. Brutalism, both the style and the philosophy, reminds us that even in the aftermath of destruction, there is room for creation—and meaning—in the raw and unadorned.

-

Dolmen – Limestone Console€7.901 incl. tax

Dolmen – Limestone Console€7.901 incl. tax -

Melancholy – Incense Burner – Aluminium€161 incl. tax

Melancholy – Incense Burner – Aluminium€161 incl. tax -

Piece Low Console€4.855 – €5.250

Piece Low Console€4.855 – €5.250 -

Sculpt – Bar Cabinet€6.640

Sculpt – Bar Cabinet€6.640 -

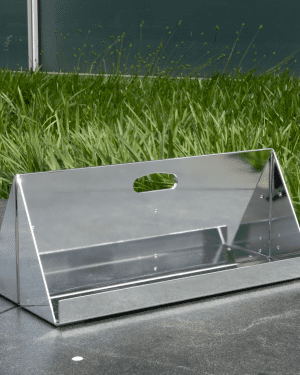

Tote Tray – Chrome Plated Aluminum€1.815 incl. tax

Tote Tray – Chrome Plated Aluminum€1.815 incl. tax -

Himalaya Lunar Vertical Alabaster Lamp€3.751 incl. tax

Himalaya Lunar Vertical Alabaster Lamp€3.751 incl. tax -

A9 Side Table – Powder Coated Steel€508 incl. tax

A9 Side Table – Powder Coated Steel€508 incl. tax -

Antigua Stone Totem€3.185 incl. tax

Antigua Stone Totem€3.185 incl. tax -

Ash Tray – Solid Aluminum€182 incl. tax

Ash Tray – Solid Aluminum€182 incl. tax -

Capella Stone Vase€1.239 incl. tax

Capella Stone Vase€1.239 incl. tax -

Axis – White Marble Side Table€6.304 incl. tax

Axis – White Marble Side Table€6.304 incl. tax -

D300 Lampion – Matte Aluminium€390

D300 Lampion – Matte Aluminium€390 -

Bevel Low Console€6.345 – €7.615

Bevel Low Console€6.345 – €7.615 -

Tenfold 5 T Metal Pendant Light€5.372 – €13.310 incl. tax

Tenfold 5 T Metal Pendant Light€5.372 – €13.310 incl. tax -

Lago – Marble Console€6.982 incl. tax

Lago – Marble Console€6.982 incl. tax -

Wrench – Low Zigzag Table€2.420 incl. tax

Wrench – Low Zigzag Table€2.420 incl. tax