Matcha do about Nothing, or Everything? A Cultural History of Chawan

The matcha bowl—known in Japanese as chawan—stands as the essential vessel in the Japanese tea ceremony, a ritual embodying profound cultural, philosophical, and aesthetic principles. As ADORNO presents its landmark collection of contemporary ceremonial vessels alongside SILENCE PLEASE x KAIKADO during New York Design Week (running from May 16-25, 2025), we offer a brief (the full history could take a an entire college course!) how these seemingly simple objects have carried centuries of artistic evolution and cross-cultural dialogue.

Origins Across Borders: China’s Influence and Early Tea Philosophy

The history of the chawan reveals a complex narrative of cultural exchange and transformation. The earliest tea bowls used in Japan weren’t Japanese at all, but Chinese imports—karamono (唐物)—brought along with tea and its associated practices in the late 12th century. In China, tea preparation and appreciation initially developed within Buddhist monasteries, where the beverage aided in meditation. The Chinese tea ceremony of the Song Dynasty (960-1279) emphasized formality, technical precision, and social hierarchy. The aesthetic values reflected in these early ceremonies celebrated refinement and virtuosity—qualities mirrored in the finest Chinese vessels.

The most revered of these Chinese imports were tenmoku bowls, discovered by Japanese monks visiting Buddhist temples on China’s Tian Mu Mountain. These conical vessels featured metallic glazes in varieties that would become legendary: nogime (禾目) with streaking patterns resembling hare’s fur, yuteki (油滴) with small spots against dark backgrounds, and the exceptionally rare yōhen (曜変) with large silvery spots surrounded by iridescence. These early karamono bowls reflected an aesthetic of controlled perfection—symmetrical forms, precise craftsmanship, and technically challenging glazes that demonstrated the potter’s mastery. Their formal beauty aligned with the hierarchical nature of early Japanese tea gatherings, which were largely displays of wealth and status among the aristocracy.

The Korean Inflection Point: Emergence of Wabi Aesthetics

The narrative of the chawan took a decisive turn in the late 15th century with the introduction of Korean bowls—kōraimono (高麗物). This shift paralleled a profound transformation in Japanese tea aesthetics, moving from the formal elegance of Chinese tradition toward the rustic simplicity that would become known as wabi-cha.

Represented here is an example of aesthetic inversion, where ordinary becomes extraordinary. The Korean bowls most treasured in Japanese tea ceremony were never created for such exalted purposes in their homeland. The ido bowls—originally common maksabal (“bowls for everything”) used by Korean peasants for daily meals—became the most coveted vessels in Japanese tea culture precisely because of their unassuming imperfections.

This process of cultural recontextualization is not unique to Japanese tea culture. Throughout history and continuing to the present day, societies have elevated objects from marginalized or foreign cultures, transforming their perceived value and meaning. These acts of aesthetic appropriation exist within complex power dynamics—what some view as appreciative cultural exchange, others may interpret as a form of cultural colonization or erasure of original context. The elevation of Korean peasant bowls to ritualistic art objects reflects this ambiguous terrain where appreciation and appropriation become difficult to disentangle.

Unlike the technically refined Chinese tea traditions, Korean ceramic practices were often more spontaneous and intuitive. Korean potters demonstrated an easy ability to allow the natural properties of clay and fire to express themselves without excessive control—a quality that would profoundly influence Japanese aesthetic sensibilities. Cultural theorist Soetsu Yanagi later articulated this aesthetic reversal in his concept of “the beauty of everyday things.”

Historical Context: Cross-Cultural Exchange During Isolation

The history of the chawan gains additional complexity when viewed against the backdrop of Japan’s changing relationship with its neighbors. While the Sakoku period (1633-1853) limited foreign contact, the foundations of tea ceremony aesthetics had already been established through earlier cross-cultural exchanges.

Prior to this period of isolation, the Japanese invasions of Korea in the 1590s had a profound impact on ceramic traditions. Korean potters were forcibly relocated to Japan, bringing their techniques and aesthetic sensibilities. This traumatic history complicates the narrative of cultural exchange, highlighting how artistic transmission often occurs within complex political contexts. Despite isolation policies, Japanese appreciation for Korean ceramics never diminished, and the aesthetic principles established through this exchange would continue to develop internally throughout the Edo period.

Japan Finds Its Voice: The Birth of Raku

It wasn’t until the late 16th century that Japanese pottery developed its distinctive voice in tea culture, most notably through the creation of raku ware. This watershed moment came through the collaboration between tea master Sen-no-Rikyū and tile-maker Chōjirō, who developed hand-formed vessels that embodied the essence of wabi aesthetics. The development of raku represents a pivotal moment when Japan no longer simply imported tea culture but fundamentally transformed it. These objects became physical manifestations of a philosophical approach to beauty that privileged impermanence, asymmetry, and simplicity.

Unlike wheel-thrown porcelain with its technical precision, raku bowls are hand-formed from porous clay, bisque-fired, glazed, and then fired again at relatively low temperatures before being removed from the kiln while still glowing hot. The resulting vessels are lightweight with natural imperfections—embodying the aesthetic principle that perfection lies in embracing imperfection. Under Rikyū’s influence, the tea ceremony evolved from an ostentatious display of wealth into a profound spiritual practice emphasizing presence, simplicity, and equality. The intimate tea room (chashitsu) became a space where social hierarchies temporarily dissolved, and participants could encounter each other as human beings rather than as representatives of their social station.

The Bowl as Philosophical Vessel

What elevates the chawan beyond ordinary object is its role as a philosophical vessel. Each bowl represents a material dialogue between cultures, between craft and nature, between intention and accident. In traditional tea practice, participants contemplate the bowl before drinking, appreciating how its form, texture, and color embody the aesthetic principles of wabi-sabi—finding beauty in impermanence and imperfection. The rotation of the bowl in the hands of the guest—examining its details before drinking—represents a moment of focused aesthetic appreciation rarely found in everyday life.

The tea bowl engages all senses simultaneously—vision in its glaze, touch in its texture, sound in how it’s placed, and taste in how it shapes the experience of the tea itself. This multisensory engagement reflects the holistic philosophy underlying the tea ceremony, where material form becomes inseparable from spiritual content.

Contemporary Reinterpretations: The ADORNO Collection

This rich historical lineage provides essential context for ADORNO’s collection of contemporary ceremonial vessels, currently being presented at SILENCE PLEASE’s Lower Manhattan tea house from May 16-25, 2025. The collection features works by 18 progressive ceramicists who have reinterpreted the traditional chawan through their distinctive material practices.

These limited-edition pieces—each produced in a series of ten—represent a contemporary dialogue with centuries of tradition. Like their historical predecessors, they navigate tensions between tradition and innovation, between form and function, between presence and absence.

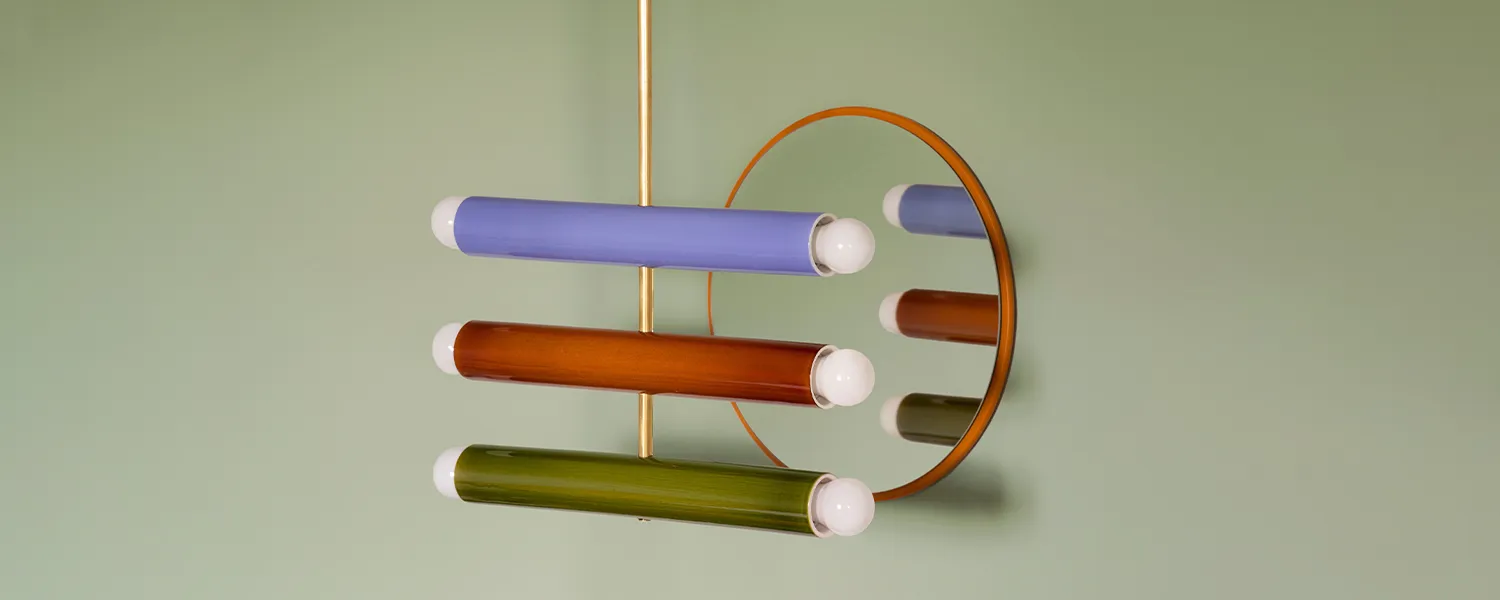

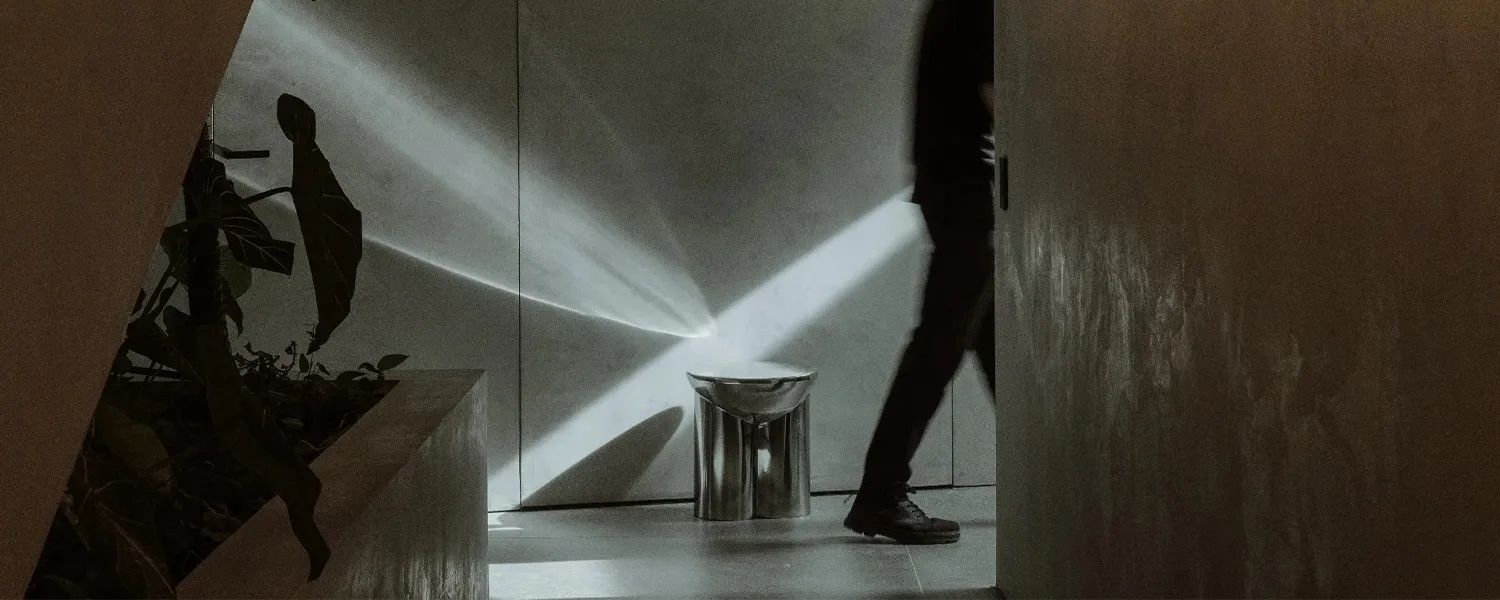

As part of the installation titled SILENT MATTERS, these contemporary vessels are being activated through ceremonial performances blending traditional Japanese tea ceremony with contemporary sound, light, and movement.

Event Details:

- CEREMONY: May 16–25, 2025 | 11:00 AM – 5:30 PM

- Advance reservations are required

- Ceremonies begin every 30 minutes

- Please arrive 15 minutes before your scheduled session

- Late arrivals will not be accommodated to preserve the integrity of the ceremony

- Mobile devices must be silenced or turned off prior to entry

- Tickets are non-transferable and non-refundable

The tea ceremony is designed by David Lavecchia, who is co-performing alongside tea master Yoshitsugu Nagano, with movement choreographed by Amy Gardner, a custom soundscape by Amma Ateria, and generative lighting by Nate Mohler.

-

Rsa (rhythmic Slow Activity) matcha BowlBy Studio S II€313 incl. tax

Rsa (rhythmic Slow Activity) matcha BowlBy Studio S II€313 incl. tax -

White & Speckled Stoneware ChawanBy FLCS€163 incl. tax

White & Speckled Stoneware ChawanBy FLCS€163 incl. tax -

Fleuve Chawan – Porcelain Matcha BowlBy SCHOEMIG PORZELLAN€144 incl. tax

Fleuve Chawan – Porcelain Matcha BowlBy SCHOEMIG PORZELLAN€144 incl. tax -

Sakura Gloop Chawan – A Sweet Drop Before The Spring RainBy STUDIO BERG€263 incl. tax

Sakura Gloop Chawan – A Sweet Drop Before The Spring RainBy STUDIO BERG€263 incl. tax -

Chawan – Mass-tinted Hand-blown Glass Matcha BowlBy OOG Objects€250 incl. tax

Chawan – Mass-tinted Hand-blown Glass Matcha BowlBy OOG Objects€250 incl. tax -

Kawa Matchawan – Limited Edition Leather-cast Porcelain Tea BowlBy Luft Tanaka Studio€375 incl. tax

Kawa Matchawan – Limited Edition Leather-cast Porcelain Tea BowlBy Luft Tanaka Studio€375 incl. tax -

Chawan – Limited Edition Mouth-blown Glass VesselBy Szkło Studio€290

Chawan – Limited Edition Mouth-blown Glass VesselBy Szkło Studio€290 -

Ignorance Is Bliss – Metal Waste Matcha BowlBy Agne Kucerenkaite€188 incl. tax

Ignorance Is Bliss – Metal Waste Matcha BowlBy Agne Kucerenkaite€188 incl. tax -

Asa – Wheel-thrown Matcha BowlBy Volupte Studio€106 incl. tax

Asa – Wheel-thrown Matcha BowlBy Volupte Studio€106 incl. tax -

‘sssst’ – Furuta Oribe Matcha BowlsBy Françoise JeffreyPrice range: €192 through €240 incl. tax

‘sssst’ – Furuta Oribe Matcha BowlsBy Françoise JeffreyPrice range: €192 through €240 incl. tax -

Midorikage Chawan – Rectangular Ceramic Matcha BowlBy Streicher Goods€375 incl. tax

Midorikage Chawan – Rectangular Ceramic Matcha BowlBy Streicher Goods€375 incl. tax -

Chawan – Cedar-shaped Matcha BowlBy ZEYNEP BOYAN€180

Chawan – Cedar-shaped Matcha BowlBy ZEYNEP BOYAN€180 -

“Root” – Ceramic Matcha BowlBy VeromOCERAMICS€188 incl. tax

“Root” – Ceramic Matcha BowlBy VeromOCERAMICS€188 incl. tax -

Samiria Raku Chawan – Ceremonial KENÉ pattern Matcha BowlBy Vale Ro€200 incl. tax

Samiria Raku Chawan – Ceremonial KENÉ pattern Matcha BowlBy Vale Ro€200 incl. tax -

Verde 10 – stoneware Matcha BowlBy Federica Paglia€460

Verde 10 – stoneware Matcha BowlBy Federica Paglia€460 -

Nuva Chawan – Glass Cup With 3d Printed ShellBy Studio Flore€125 incl. tax

Nuva Chawan – Glass Cup With 3d Printed ShellBy Studio Flore€125 incl. tax