Greem Jeong Examines Substance vs. Material

Among Seoul’s historic palaces, Greem Jeong creates work that embodies her city’s dynamic spirit. Here, traditional hanok houses stand beside soaring glass towers, a constant dialogue between past and present that flows through her design practice. After her studies in France taught her to work without creative constraints, Greem returned to Korea where she discovered how the country’s precision could realize her most ambitious ideas. This combination of European experimentation and Korean craftsmanship results in pieces that feel at once thoughtfully conceived and delightfully unexpected.

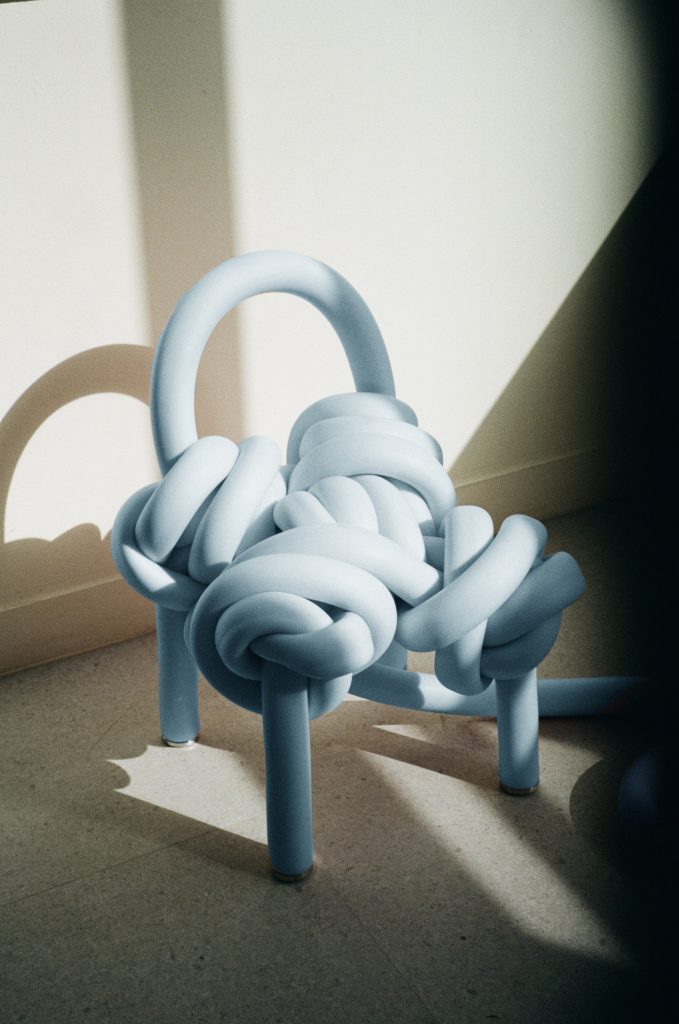

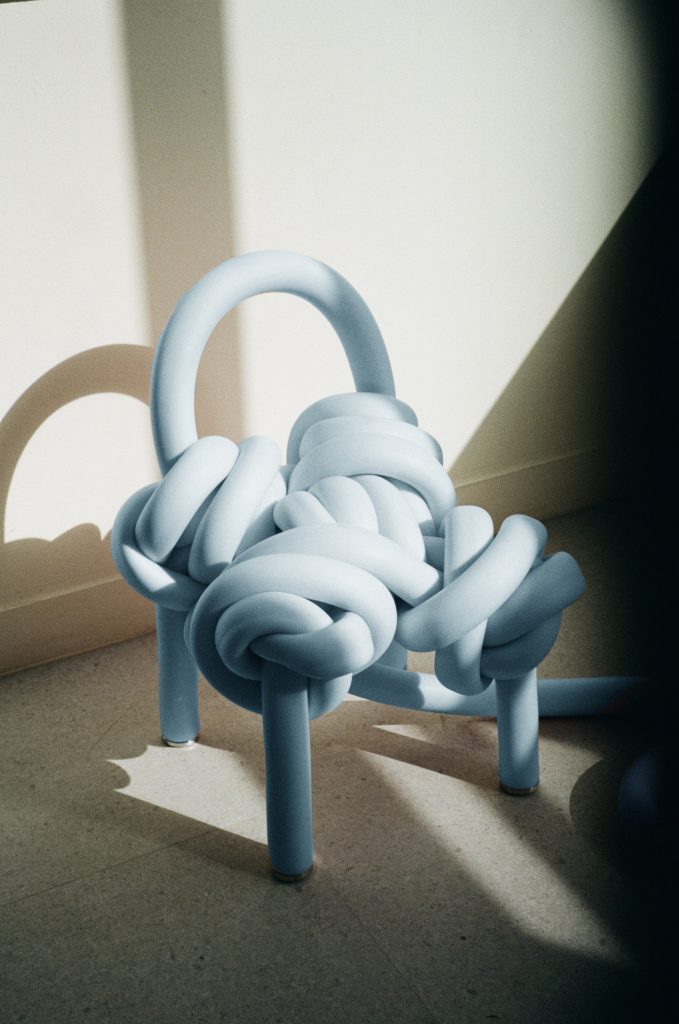

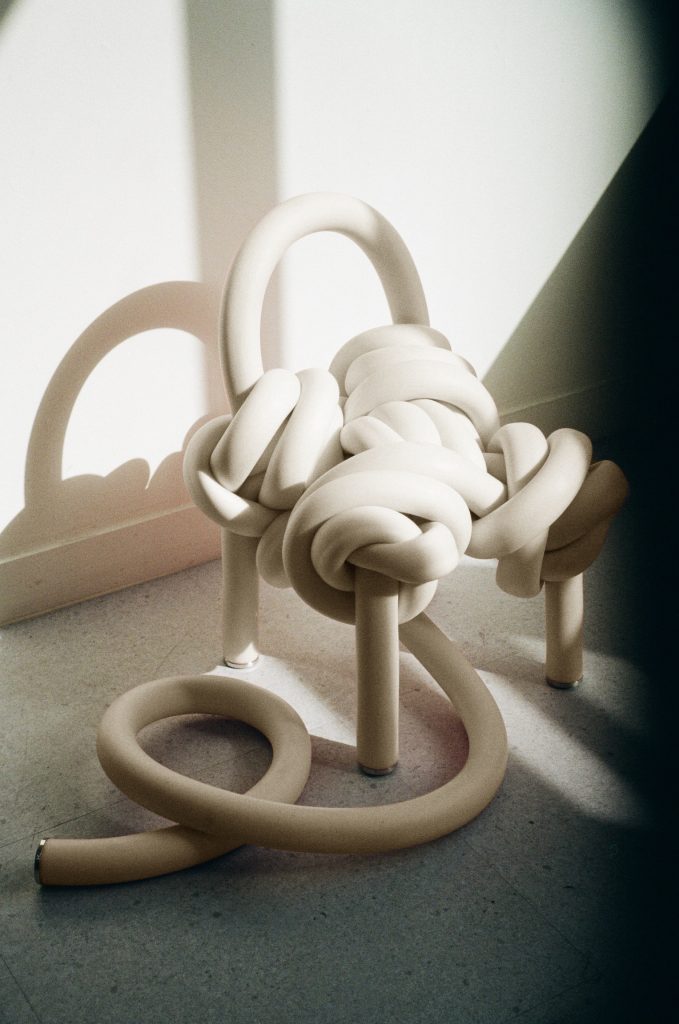

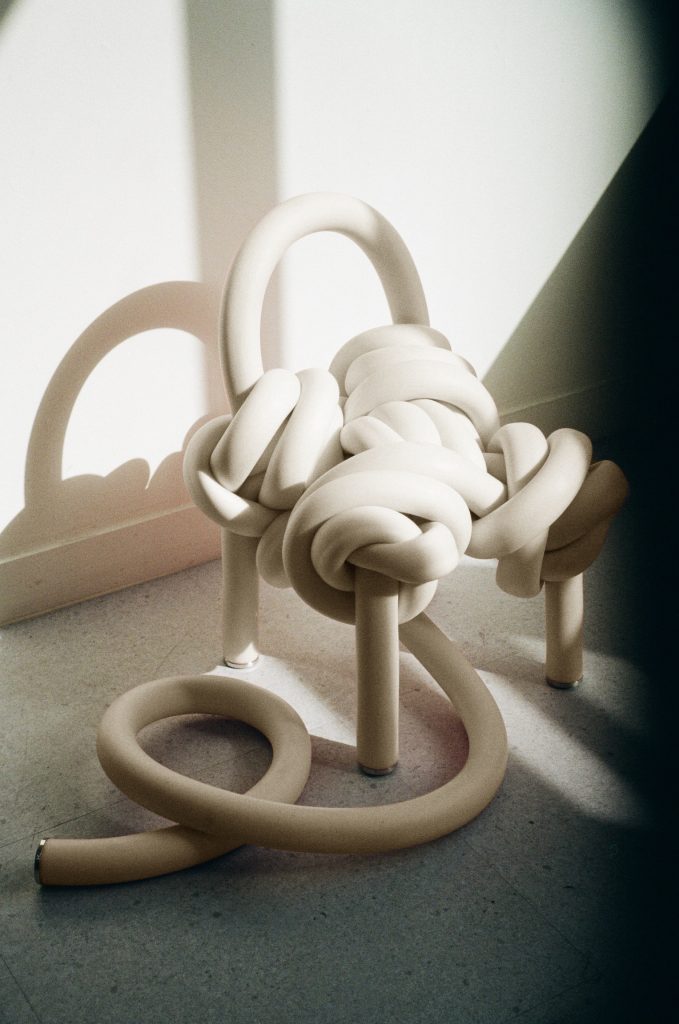

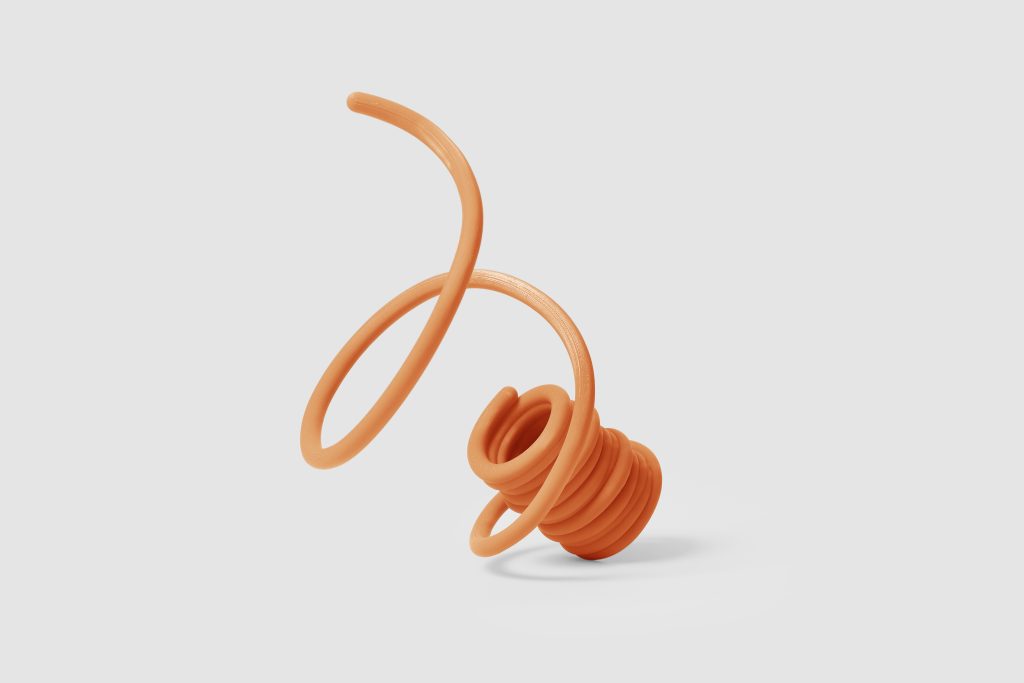

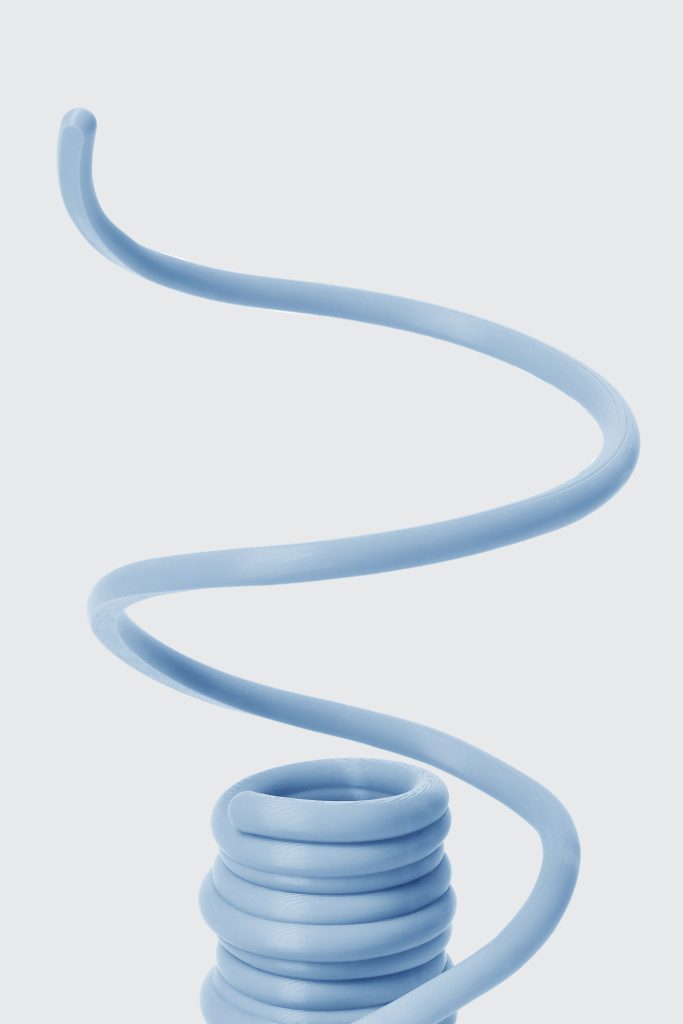

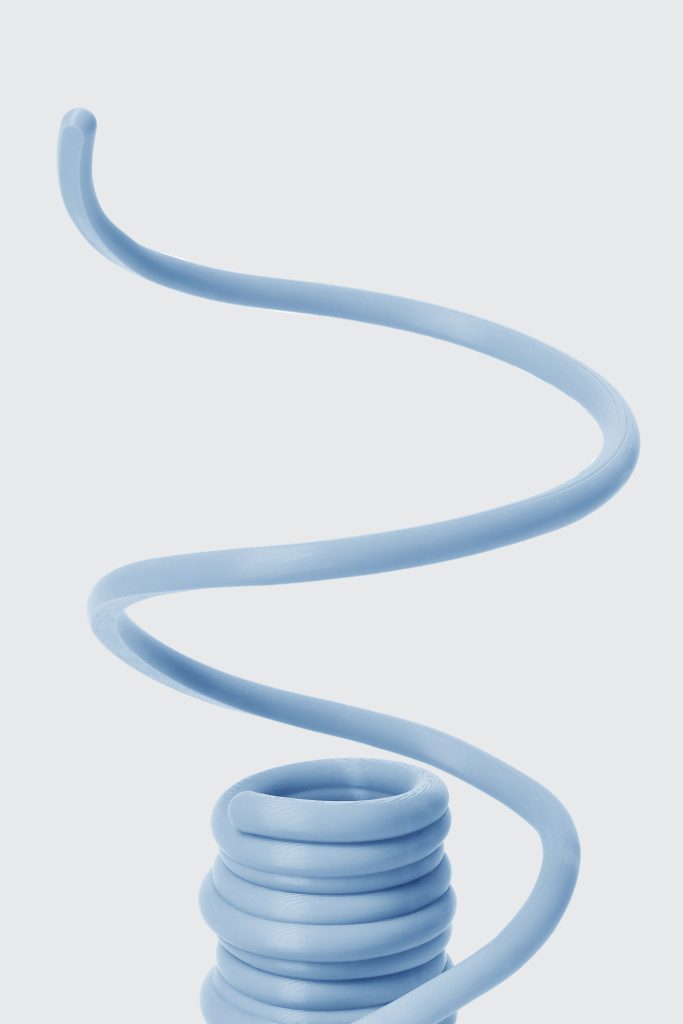

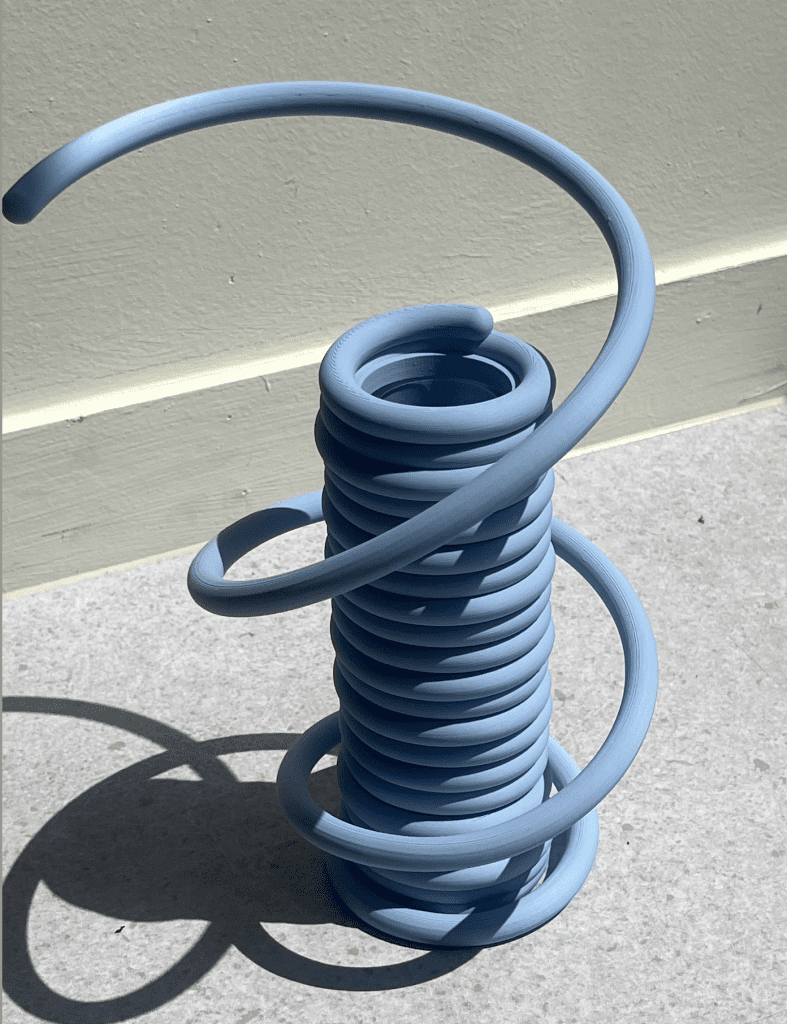

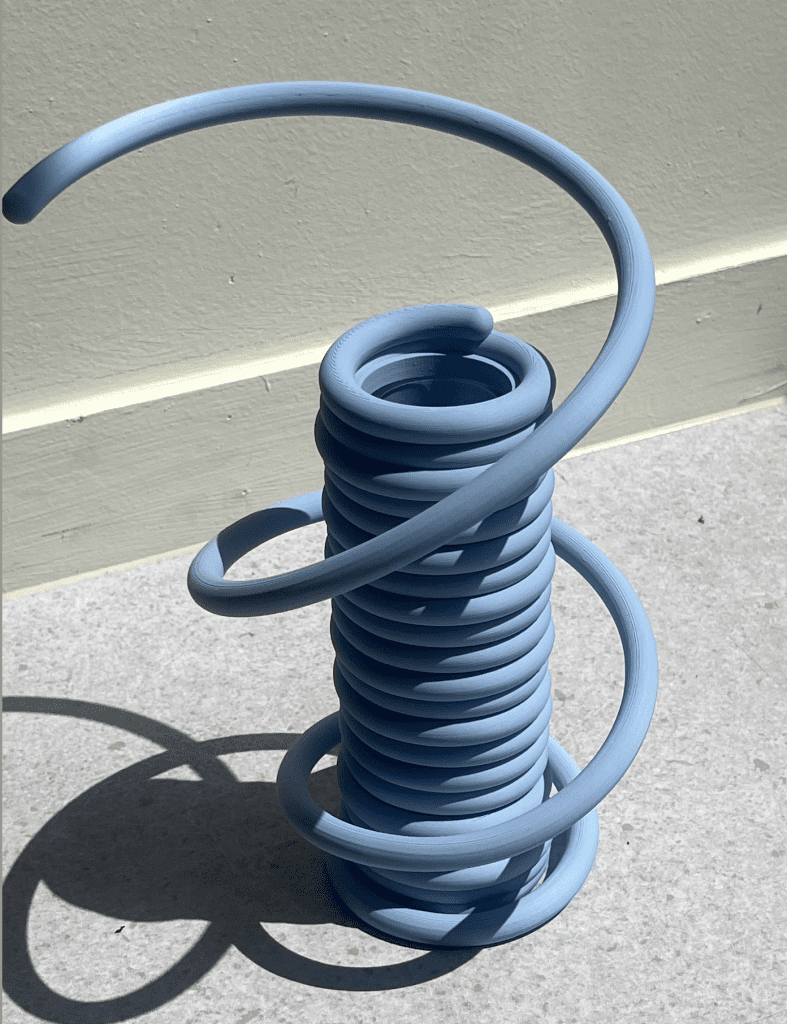

The Mono collection perfectly demonstrates her ability to elevate everyday materials into extraordinary forms. Beginning with industrial silicone tubes, typically concealed within building walls, Greem crafts furniture that appears to capture movement itself. Each piece exists as a line suspended in motion, drawing viewers in with bold colors and fluid shapes before surprising them with an unexpected tactile softness. This innovative approach has resonated far beyond furniture design, catching the attention of fashion house Bottega Veneta, where her sculptural language found new expression in luxury accessories.

Greem’s work brings a refreshing lightness to contemporary design. Her pieces carry an assured playfulness, reimagining what furniture can be while maintaining a sense of joy and discovery. This collection showcases her distinctive approach, where each piece begins not with traditional furniture archetypes but with a simpler question: what makes an object invite sitting? The results occupy that intriguing territory between sculptural form and functional design, where utility meets abstraction. Through these pieces, we see how Greem continues to push the boundaries of material and form, creating work that challenges our expectations of what furniture can be.

Growing up in Seoul, you experienced a blend of historic architecture and contemporary urban life. How have these contrasting environments shaped your design approach?

Seoul is a city with a unique charm where past and present coexist. With over 600 years of history, the city holds many historical sites and cultural heritage from the Joseon Dynasty. It’s a city where tradition and modernity are in harmony. I actually live in a hanok near Gyeongbokgung Palace. When I try to transform and develop my work, I find myself contemplating modern and popular elements, and in doing so I often discover newness in old things around me. When I combine aesthetic elements I want to emphasize with modern and personal elements, I find that the beauty is maximized. Traditional elements need not be seen as outdated but can be utilized to create new value.

Additionally, Seoul is a rapidly changing and developing city. New trends are quickly adopted, and the city’s infrastructure and services are constantly innovating. Sometimes these aspects can place Seoul’s residents in an overly competitive society, making them tired and lethargic. However, this is also why Seoul remains a city where you can always feel a dynamic and youthful energy. It’s always dynamic, trying to pursue new things. I also continuously try new things while being stimulated by the city.

After working in both European and Korean design scenes, how do you navigate between these two scenes known for a difference in design sensibility and approaches?

What surprised me while receiving an art education in France was that they don’t start by precisely defining something. The fact that established frameworks or rules are vague means that the direction and way of thinking in developing ideas is very open. This allows you to approach things more diversely when you try to create something, both conceptually and methodologically. And in Korea, the well-established manufacturing companies and craftsmen’s quick and clear feedback is very helpful in testing and actualizing ideas I developed in the past. Korea places a lot of importance on strict standards and discipline. As a result, we’re ingrained with the idea of handling work quickly and accurately. I think this acts as a great advantage in carrying out projects and exhibitions.

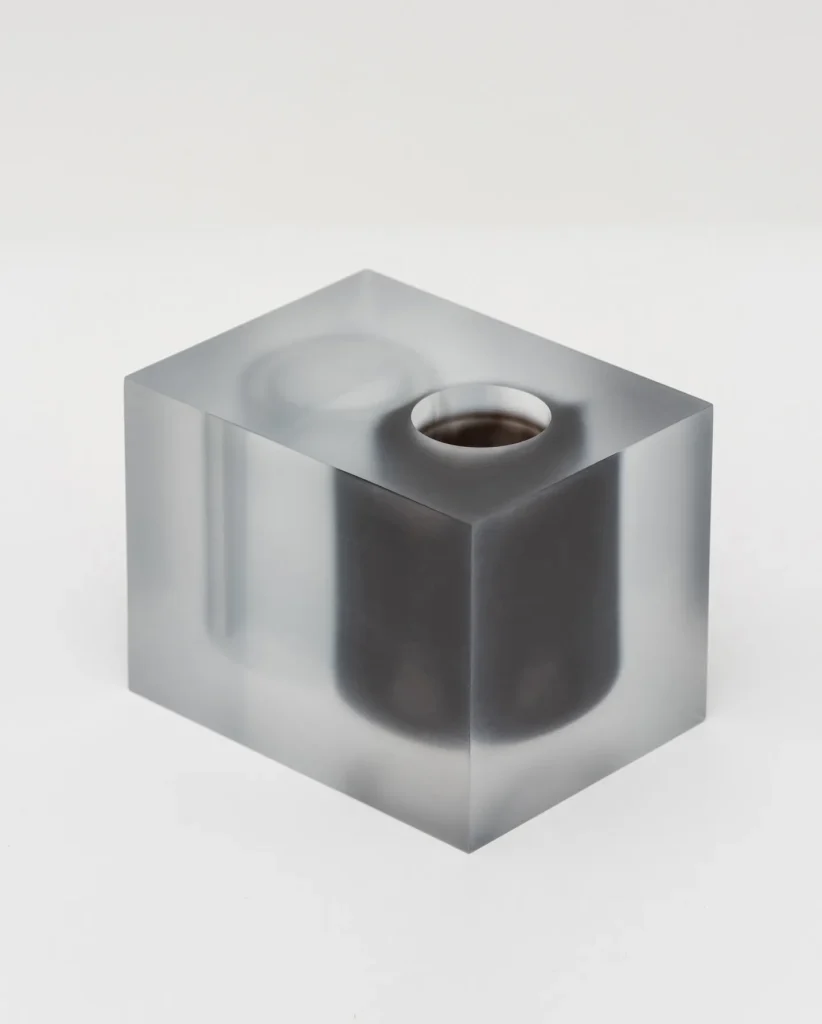

Before discovering silicone tubes, you experimented with various materials like resin and acrylic. How did these early material explorations shape your current practice?

My current work methods have been really influenced by the experience of experimenting with various materials. The process of handling different materials not only improved my technical proficiency, but also helped me develop the ability to incorporate and apply elements from multiple angles in creating my work. While studying in France, I deeply explored the difference between “Matière” (substance) and “Matériau” (material), which influenced my thought process and approach to my work.

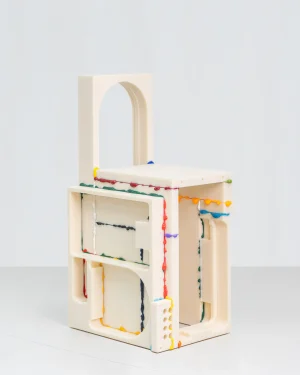

When you’re repeatedly doing work that you’re familiar with, you discover physical disadvantages, which leads to finding other materials to complement them, and through discussing production methods with experts, you discover new possibilities. Initially, I mainly worked with industrial materials like iron and silicone, but before that, I learned ceramic techniques and later expanded to acrylic, glass, marble, various types of metals, 3D printing, and more traditional materials. Beyond just simply experimenting, this expansion became an important resource that allowed me to create pieces more diversely and expand my ideas. This helps the piece evolve to be richer and more multi-layered.

What made you choose industrial silicone tubes as Mono’s primary material, and how does this choice play into the tactile and visual experience for your audience?

I still remember the overwhelming impression I felt when I was freely arranging bold and long linear materials in a space. In contrast to their strong visual presence, I thought their soft texture would convey both unexpectedness and freshness to the audience. Not only does it provide viewers with a unique tactile experience, but it also showcases the abstractness and playfulness of lines through form. I wanted to create functional objects or sculptures that are abstract while transcending stereotypes.

Additionally, the material’s flexible properties maximize the flow of organic lines while providing sculptural freedom. This aspect really influenced how I started my work and then continued to develop and derive pieces from it.

Viewers experience more than just seeing ‘lines’ when looking at my work; they experience sensory contrasts and unexpected elements in its flow and materiality. While the work visually dominates the space, it also stimulates the desire to touch, and by arousing curiosity about its function or identity, it leads to more intuitive communication with the audience.

The Mono collection features bold and playful color choices. How do you approach selecting the palette for each piece, and what role does the surrounding space play in shaping those decisions?

The way I choose colors varies depending on the situation. For exhibition pieces, I select colors that match the exhibition theme and atmosphere, and when collaborating with brands, I use their key colors to maximize their brand identity. I might choose colors that complement the piece’s form and material, or sometimes envision specific colors before conceptualizing the work. I also select colors by imagining the space where the piece will be placed. Whenever possible, I prefer to first be aware of and conceptualize the space where the piece will be placed. This way, the work doesn’t simply occupy space but interacts organically with it. I believe a piece can reconstruct the space and give it new dynamism. It’s about achieving harmony with the environment beyond being an independent object.

Rather than following furniture conventions, Mono strips away traditional elements. What discoveries emerged from this reductive approach?

When I first started working, I began with the idea of creating ‘something you can sit on.’ However, I didn’t definitively define it as a ‘chair.’ Usually, when you think of the word ‘chair,’ you naturally imagine a form with four legs, a backrest, and a seat. I wanted to break free from these stereotypes and approach it sculpturally.

My first piece was born while exploring forms where lines gather to create surfaces, and surfaces flow to become lines again. It was a structural object with repeating arch-shaped lines. Through this approach, I was able to gradually expand the Mono series in a variety of ways.

While most of Mono explores flexible forms and bold colors, the glass tops introduce a different geometry and expression entirely. What inspired this juxtaposition of materials?

This too follows a similar context to the approach I mentioned earlier. The work began by incorporating planes into lines, the basic elements of form, as if drawing a picture. I thought about different combinations while combining and stacking materials with different physical properties and textures. I simply used transparent materials for the surface portions to emphasize the lines, which are the main elements. Through transparency, I wanted to highlight the flow of lines and structural beauty. Sometimes I would add colored acrylic to create color combinations. This harmony creates a unique balance through the contrast of form, color, and material properties.

As you continue to experiment with new materials and forms, where do you see your practice heading next?

I would like to slowly continue working with partially adopting the najeonchilgi (mother-of-pearl inlay) technique that I recently showcased at my Seoul solo exhibition. I believe this technique, which embodies the essence of Korean traditional crafts, has the potential to further emphasize my identity and originality as a Korean. Also, I’m very interested in how traditional beauty can be harmoniously merged with modern technology and aesthetics.

Additionally, I’m challenging myself with public art pieces. The sense of achievement from creating large-scale works and the ability for citizens to naturally encounter art in public spaces is one of the things that attracts me to public art.

At the same time, I plan to continue creating small-scale objects so that anyone can easily enjoy art in their daily lives. For this ADORNO project, I participated by selecting pieces focusing on these everyday art objects.

-

B. S. P Series “the Original”By Atelier SOHN€7.750€7.750

B. S. P Series “the Original”By Atelier SOHN€7.750€7.750 -

Ceramic Nacre – Mosaic Tile DrawersBy STUDIO KIMBYUNGSUB€0€0

Ceramic Nacre – Mosaic Tile DrawersBy STUDIO KIMBYUNGSUB€0€0 -

Narrative 001 – Stainless Steel / Wood ChairBy STUDIO KIMBYUNGSUB€10.000 incl. tax€10.000 incl. tax

Narrative 001 – Stainless Steel / Wood ChairBy STUDIO KIMBYUNGSUB€10.000 incl. tax€10.000 incl. tax -

Objects Of Function No.2401 – Stainless Steel Coffee TableBy Park Eunchong Studio€3.188 incl. tax€3.188 incl. tax

Objects Of Function No.2401 – Stainless Steel Coffee TableBy Park Eunchong Studio€3.188 incl. tax€3.188 incl. tax -

Aluminum Veneer BenchBy Bureau.parso€4.750 incl. tax€4.750 incl. tax

Aluminum Veneer BenchBy Bureau.parso€4.750 incl. tax€4.750 incl. tax -

Aluminum Veneer VaseBy Bureau.parso€675 incl. tax€675 incl. tax

Aluminum Veneer VaseBy Bureau.parso€675 incl. tax€675 incl. tax -

Aluminum Veneer LampBy Bureau.parso€1.750 incl. tax€1.750 incl. tax

Aluminum Veneer LampBy Bureau.parso€1.750 incl. tax€1.750 incl. tax -

Crest And Trough Series – Chrome BenchBy Dongwook Choi€4.250 incl. tax€4.250 incl. tax

Crest And Trough Series – Chrome BenchBy Dongwook Choi€4.250 incl. tax€4.250 incl. tax -

Crest And Trough Series – Chrome Stool / Side TableBy Dongwook Choi€3.250 incl. tax€3.250 incl. tax

Crest And Trough Series – Chrome Stool / Side TableBy Dongwook Choi€3.250 incl. tax€3.250 incl. tax