The Question Beneath the Surface: Jaeho Lee’s Undress House

Jaeho Lee doesn’t necessarily want his work to be defined in any specific way. At least, not in the ways we’re used to interpreting or categorizing art. “It’s not meant to be resolved or neatly interpreted,” he explains from his Seoul-based studio, Undress House. “But I hope it stays with them in some way, maybe as a slight discomfort, a question, or even just a passing sense of amusement.”

This is the paradox at the heart of Undress House: creating objects that function as furniture yet resist easy categorization, pieces that serve practical needs while simultaneously questioning what practicality means. His “ironic functional objects” stand somewhere between utility and art, between the familiar and the strange, inviting reconsideration of our assumptions about form, function, and how we understand both.

Incompleteness as Philosophy

The name “Undress House” emerged from Lee’s desire to avoid being “defined by a fixed form.” For him, “Undress” points toward a state of incompletion, a space that remains deliberately undefined. “‘Undress’ reflects my wish not to be defined by a fixed form,” he explains. “It can mean unveiling, but for me it also suggests something that hasn’t yet fully formed — a space that remains open and undefined.” “House” serves not as a physical structure but as a “conceptual space that can hold whatever I choose to explore.”

Openness is through-line in Lee’s work. His intention isn’t necessarily to solve problems or suggest answers, as many traditional studios do. Instead, he aims to raise questions through pieces that function with what he describes as ‘a small rupture’—a disruption that prompts viewers to reconsider form, function, and beauty.

The approach reflects a deeper understanding of how meaning is constructed. Rather than imposing singular interpretations, Lee creates works that invite personal discovery. “Each person reacts differently, and I always find that really interesting,” he notes. “I just hope people see it in their own way and have their own experience. There is no right answer.”

Material and Memory

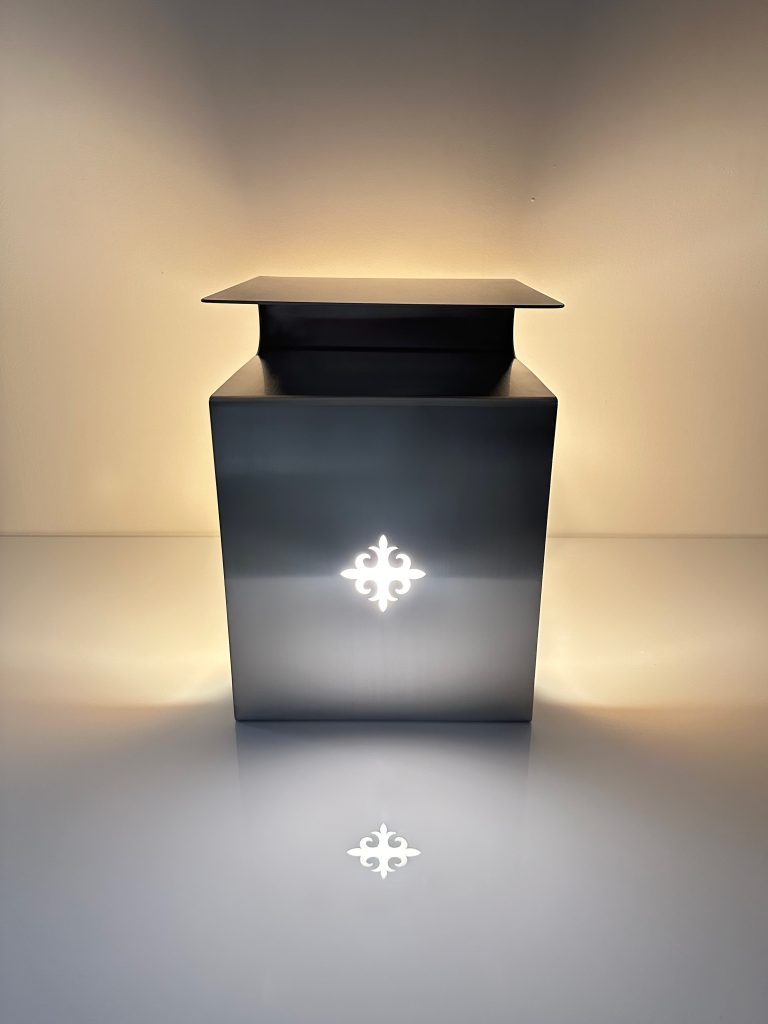

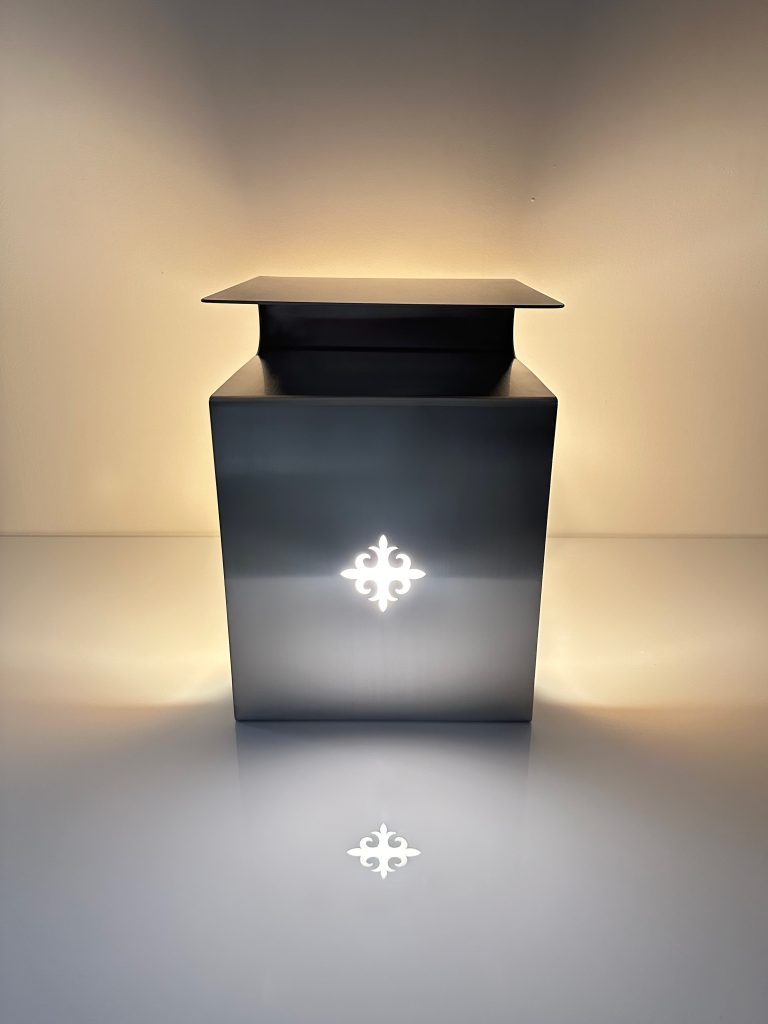

The creative process of Undress House often begins with what Lee calls “the conceptual weight of a material.” His Peace After the Burn art objet demonstrates this material-driven methodology. The work incorporates black crystal sand—fragments of stone broken down and reformed through resin into something new. This material process became a metaphor for personal reconstruction: “how our past memories and pieces of past self come together and become who I am today.”

This material sensitivity extends to his Fur Low Table, where the collision of cold stainless steel and soft fur creates what Lee calls “unexpected harmony.” The contrast operates on multiple levels—visual, tactile, and emotional. “Cold stainless steel often feels distant or rigid, while fur evokes softness and warmth”. By combining materials that feel “emotionally opposite,” he creates encounters that disrupt familiar sensations and perceptions.

The piece demonstrates Lee’s belief that materials carry inherent emotional weight. “I was less focused on tactility itself and more interested in the emotional reactions materials can trigger,” he explains. “By combining two materials that feel emotionally opposite, I wanted to see if we could experience something beyond familiar sensation, something that challenges how we understand what we see and feel.”

Connection and Constraint

Perhaps nowhere is Lee’s openness to discovery more evident than in his Linked Chair. The piece began with a chance observation: two chairs chained together in a park, an image that struck him as “both beautiful and strangely suffocating.” This moment of recognition—seeing connection and constraint as simultaneous realities—became the conceptual foundation for a work exploring the “inherent irony of relationships.”

The chair’s stainless steel rings move freely yet remain bound to the structure, embodying how “relationships grant us freedom while inevitably restricting us.” But Lee’s most revealing discovery came after the piece was complete: the unexpected sound created when the rings collide. “The sound wasn’t something I planned from the beginning,” he admits, “but when I heard the stainless steel rings collide, I realized it added another layer to the piece.”

This willingness to embrace the unplanned reveals a mature artistic sensibility. The collision sounds, which Lee describes as potentially “beautiful, but also distracting or slightly irritating,” perfectly echo the piece’s central theme: that human connection contains opposing forces simultaneously. “Depending on how you hear it, the sound can feel beautiful, but also distracting or slightly irritating. It reminded me that the state of being linked, of being together, can hold two opposing meanings at once.”

Rethinking Rest

Lee’s upcoming work continues this exploration of contemporary contradictions. His project combining a Tesla car seat with a traditional rocking chair structure addresses how concepts of rest have evolved through technological transformation. “I was interested in how the rocking chair, once a symbol of rest, has become almost obsolete in our fast-paced world,” he explains. “Meanwhile, rest today often happens inside a self-driving car, in motion and surrounded by screens.”

This piece exemplifies a broader inquiry of Undress House into what lies “beneath the things we take for granted.” By connecting two different forms of rest—one rooted in stillness and tradition, the other in movement and technology—he questions fundamental assumptions about comfort, leisure, and human needs in contemporary life. “By connecting these two different forms of rest, I wanted to question what rest truly means to people today.” The work demonstrates how Lee uses temporal juxtaposition as a design tool, bringing together objects from different eras to illuminate shifts in human behavior and values.

Working with Imperfection

What distinguishes Lee’s approach is his refusal to seek perfection. “In a fragmented world, I try not to seek perfection, but rather an honest representation of my own incomplete self,” he reflects. This embrace of incompleteness isn’t a limitation but a strength, allowing his work to remain open to interpretation and discovery. This philosophy extends to his understanding of function itself. “I don’t think my works are without function,” he clarifies. “The function may not be the first thing you notice, but it is there in a minimal form. I am more interested in what happens when that minimal function holds something deeper.”

Lee’s approach to ambiguity reveals sophisticated thinking about the relationship between maker and audience. “That ambiguity pushes me to question the balance between function and concept,” he explains. “I am not trying to exclude practicality, but to explore what it means, especially because ideas of what is functional or beautiful vary from person to person. For the viewer too, it leaves room not for fixed answers, but for personal questions to surface.”

Questions Without Answers

“I want viewers to feel a small rupture in how they think about form, function, beauty or even themselves,” Lee concludes. The “ironic functional objects” of Undress House function precisely because they resist easy categorization, because they maintain space for wonder, discomfort, and personal discovery.

Undress House is a space for interrogation, for the kind of honest incompleteness that leaves room for growth, change, and the endless possibility of seeing differently. His work offers something increasingly rare: the opportunity to encounter the unexpected, to be surprised by our own responses, and to discover that sometimes the most profound questions are the ones we never thought to ask. The question that drives his practice remains open: “Maybe what I am still trying to understand is how seemingly opposite ideas, perceptions, or concepts can meet in the middle, and how that meeting point can sometimes create unexpected harmony or a new kind of beauty.”