Hot Wire Extensions: Turning Waste Products into Functional Art

“Aside from the material aspects, I believe that it is important for new processes to also explore new aesthetics. Only then can we engage society in looking at the current material landscape problems and think about waste materials in ways that can inspire and even be valuable in the future.”

– Fabio Hendry of Hot Wire Extensions

View the Hot Wire Extensions showroom, including “Object 13” from the “Native” Collection

As technology continues to become more advanced and sustainability becomes a more salient issue, finding ways to connect these two could pave the way for revolutionary efforts not only in terms of renewability, but also in design.

This task is currently being undertaken by Hot Wire Extensions, a design studio that has created an innovative way to turn waste into beautiful pieces of furniture, fixtures, and more. Headed by Fabio Hendry, a Swiss designer and material researcher who has extensive experience working for a variety of institutions and clients, Hot Wire Extensions’ material of choice is SLS 3D nylon powder. A byproduct of SLS 3D printing, this material is not currently being recycled.

Using a fascinating process that combines both technical and organic aspects, HWE’s pieces are created by “cooking” copper tubes surrounded by sand and the aforementioned nylon powder, causing everything to melt together and eventually cool and harden into a stone-like material. This unique technique allows for the creation of a wide variety of pieces, from the natural, abstracted forms of the “Native” series, to the readable, concrete forms of the “Play” series, to the geometric “Hotel” series, which focuses on creating lights that are stripped-down versions of the ornate fixtures seen in historic Swiss hotels.

Could you explain the process for creating one of your pieces?

The process of making a Hot Wire Extensions piece always starts with looking and exploring what is around. It is how the process itself was developed, through looking at nature and critically analysing manufacturing techniques and industries. Once I have decided what kind of thing the object will be – stool, light, or sculpture for example, I create the form from a copper tube, the diameter of which depends on whether it will be a light or not.

A resistance wire is then fed through the copper tube, this will eventually be connected to an electrical source. A resistance wire is a wire that makes it difficult for electricity to flow through, and because of this, the resulting friction is turned into heat, something that is essential to the process.

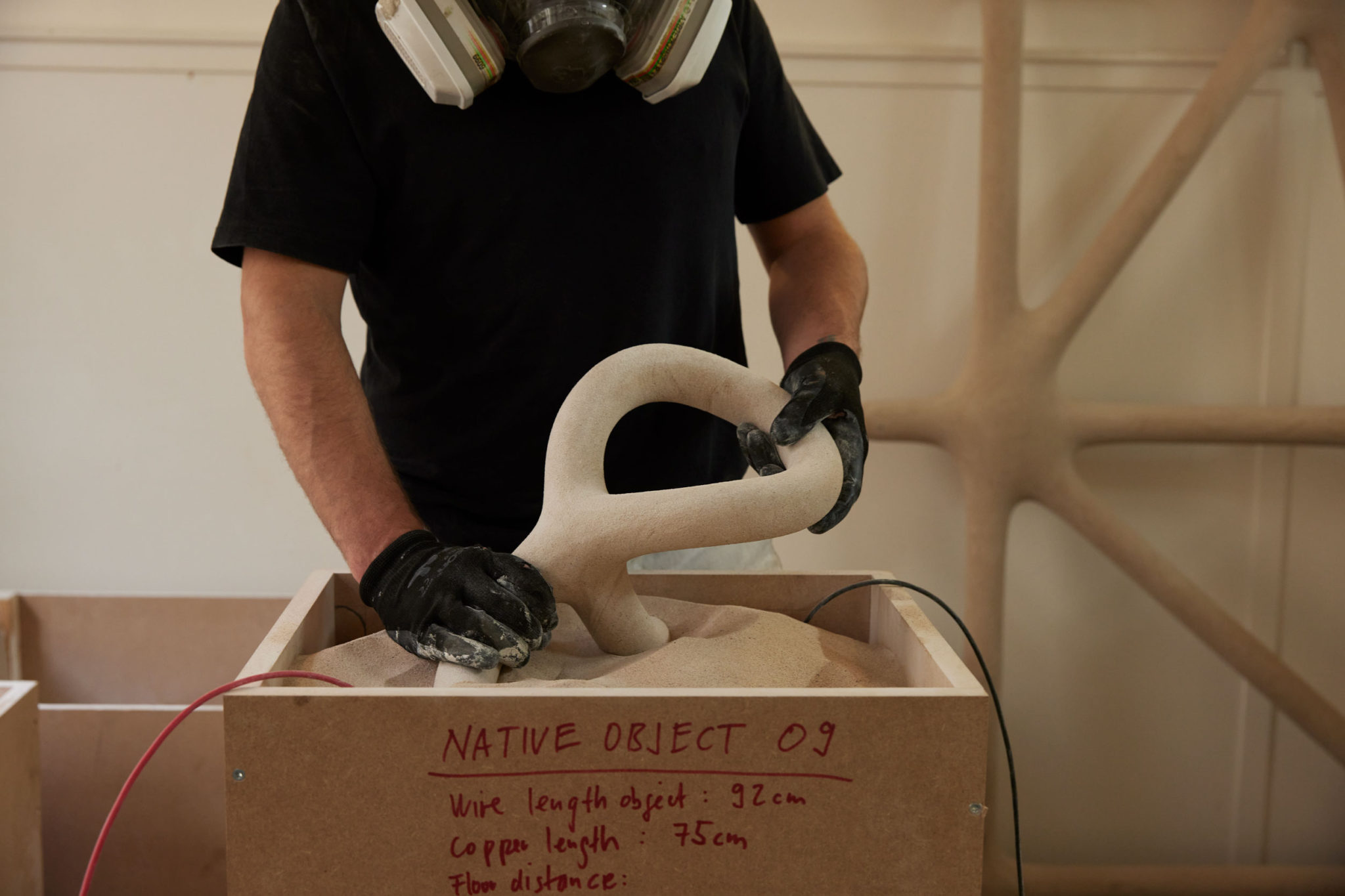

Once the hybrid tube is ready and formed, it is placed inside a container, which is then filled with a mix of sand and waste nylon powder. An electrical current is then sent through the wire causing it to heat up. The heat makes plastic particles melt and, because they are surrounded by the fine sand, they melt together in place. As well as acting as a filler material, the sand also acts as a conductor, moving the heat away from the wire which means that the longer you ‘cook’, the thicker the objects get. Most of the pieces are heated between 30-40 minutes.

After this heating process, as the objects cool down, the material hardens and bonds itself together, creating solid and robust structures.

For the lights, a thicker copper tube is used, which means the resistance wire can be removed once the piece is cool and electrical cables can be fed through to join with LEDs.

We are experimenting with different diameters of copper tubes and are currently developing a series of radiators, where we can utilise the larger diameter to allow water to flow through. Because sand is a good thermal conductor and also stores heat well, it can really open up new possibilities of how the design of radiators is approached.

Waste SLS 3D-printing nylon powder is an extremely unique material to use in design. How and why did you decide to begin using it?

The initial foundation of the process was laid about five years ago. I was graduating from the Royal College of Art in London and there was an abstract idea to develop a new type of process that could close the gap between a sketch, a prototype, and final product. The project started with the simple idea of using a heat source, which could attract and transform its surrounding material. Together with a fellow student, Seongil Choi, we looked into different aspects of heat and its possible sources. This led us to experiment with Nichrome-wire, which is easy to shape by hand, doesn’t require any tools, and can be heated up by simply passing an electrical current through it. We started to dream of objects that can be instantly and easily created, almost like making a drawing.

After many weeks of hands-on experimenting with various plastics in countless forms, almost by mistake we discovered the Nylon powder from SLS-3D printing. Originally, we were not aware that it was a waste material, but the discovery and realization gave our research even more purpose and drive to continue. Although effective, the process [of 3D printing] is extremely wasteful. In the case of nylon SLS, some 44% of the fine nylon powder in the printing chamber is commonly discarded after production. From talking to people in the industry, it was clear that there was a demand to put this material to use and a lack of ideas of how to do so.

Many years have passed since this initial development, but for me, it is a continuous journey to optimise and rationalize the process. I am always exploring the world around me, and testing new waste or overlooked materials that may be able to be incorporated into the Hot Wire Extensions process.

Aside from the material aspects, I believe that it is important for new processes to also explore new aesthetics. Only then can we engage society in looking at the current material landscape problems and think about waste materials in ways that can inspire and even be valuable in the future.

L-R: “Object 09” from the “Native” Collection in Teal, “Object 02” from the “Hotel” Collection in Sand, & “Object 12” from the “Native” Collection in Dusty Pink

Is the final piece able to be accurately predicted when first creating a model with wires, or is there a degree of unpredictability? How does this affect your approach to designing a piece?

For a long time, the Hot Wire Extensions process was very unpredictable. But this unpredictability can be leveraged as a source of inspiration and a tool to design and develop new objects. The process is very unlike traditional manufacturing techniques where from a drawing board a piece can be mechanically reproduced one to one, without any error. Having said that, we have been gathering data and information from previous pieces, which now allows us to be able to predict how thick an object will grow and what heating times and temperatures are required for a desired outcome.

For more complicated designs that involve weaving, crossing over, or intersecting wires, we always do hands on prototyping. However, we are working on a digital tool via Grasshoppers which will eventually allow us to predict the growth of complex structures. We think it is important and want to continue with both ways of working. Hands on experimenting feeds into new ideas and designs, but if a client has something in mind for example, it is good to have the option to be able to model it for them.

Your “Native Collection” and “Play Series” both showcase the organic nature of your design. Could you describe what draws you to this type of style?

With the “Native Collection” and “Play Series”, we were really interested in creating objects that are dynamic and playful. Wires can be shaped and formed into anything you like, they can be joined and knotted, and we wanted to highlight that, while the material is very robust, it is possible to create objects that flow and intertwine. The process was initially inspired by how vines grow around trees, and with the “Native Collection”, I really wanted to go back to nature in this sense. I also wanted the explore the possibility to create objects that are ‘raw’ and natural and to make the material a key part in the aesthetic of the pieces.

When designing the Native pieces, it was a very intuitive process, working freely and allowing for experimentation. One piece might have taken one hour or twenty seconds, but the focus was always on expression and free form. We were also interested in exploring unique pieces for the “Native Collection” and so the way in which the pieces were created reflects this, it is very difficult to recreate them with the same dynamism and feeling.

With both collections, we were interested in exploring known and unknown forms. The “Native Collection” was based on looking at the surroundings and translating unique forms within the objects that are alien and open to interpretation. With the “Play Series”, the forms are much more readable, they allow for associations and with both collections we were interested in playing with this juxtaposition.

The “Hotel Light Series” seems to be based around a much different aesthetic than the “Native Collection” and “Play Series”. What was your source of inspiration for this series?

With the “Hotel Light Series”, I wanted to explore the archetypal forms seen in historic Swiss hotels. Often the lights in these hotels are made from metal with intricate forms and decoration. This is something that doesn’t make sense to attempt to recreate with the Hot Wire Extensions process. The aim of the “Hotel Light Series” was rather to analyse and strip everything down to its core geometric form and create pieces that evoke and hint to the originals instead. It is also the first series of lights that are all wall-mounted.

L-R: “Object 05” from the “Hotel” Collection in Yellow, White, & Dusty Pink

Many of your pieces are lights. What role does light itself play in these pieces?

In the past, Hot Wire Extensions was generally more preoccupied with seating, but I became increasingly interested in lighting because it seemed to fit so well with the process. The fact that the lights are made from a hollow copper tube, gave me an opportunity to utilise and take advantage of this. Through experimentation, I discovered that not only does the process really lend itself to lighting, but the pieces are also enhanced through the use of light.

Light allows the pieces to cast shadows, to add an element to the piece that moves and changes. The form may be static, but shadow and light allow each piece to be dynamic. For me, light is almost like a cherry on top of an object, it finishes the form.

Bio

Hot Wire Extensions is a young sustainable design brand led by Swiss designer and material researcher Fabio Hendry.

Exploration, collaboration and sustainability are central to Fabio Hendry’s design philosophy. Fostering material innovation and experimental engineering, Hot Wire Extensions presents an innovative manufacturing process, applied to a range of products, furniture, installations and special commissions. The process was developed as a response to the changing material landscape, critically analysing and questioning the consequences of technical innovation. With innovation comes new challenges in waste management, shifting design aesthetics and changing consumer trends. Hot Wire Extensions seeks to explore these questions through utilising waste material and developing a process that lends itself to bespoke designs without impacting or having to change the production process.

Using waste SLS 3D nylon powder, a material that is currently not recycled, and inspired by the way a vine grows around a tree, a nichrome wire is shaped and placed within a container filled with nylon powder and silica sand. An electric current is sent through the wire, causing the mixture to solidify around the form leading to endless possibilities in shape, scale and application.

The Hot Wire Extensions objects are defined by the process’ unique organic bone-like aesthetic and characterised by the mindful exploration of material landscapes.

Fabio Hendry is a Swiss designer whose work seeks to explore new potentials for overlooked matter from architectural systems to materials. Hendry is interested in exploring disruptive approaches to industrial manufacturing, revealing alternative systems of production. It is his belief that design practices and ecological theories can be merged to allow us to critically consider our material landscape. Hendry is interested in the analysis of innovative and future industries and takes inspiration from nature’s ability to adapt and reconstruct. His innovative products and hands-on experiments explore the boundaries between crafts and industry, ranging from furniture to sculptural objects and spatial installations.