Faissal El-Malak: Intersections of Textile & Clay

“Conceptually, these pieces represent the notion of colourful, traditional craft acting as the very pillar that shapes the space and buttresses it to be a functional vessel. Together, these elements form a symbiotic balance between aesthetics and functionality.”

– Faissal El-Malak

View Faissal El-Malak’s works, including the “Spool“ Vase

The Palestinian design scene can be viewed through its focus on traditional craftsmanship, the exchange of knowledges, and the interweaving of identity and place. It is a scene that can be found both in the state of Palestine itself as well as abroad in its many diasporic communities, each space hosting designers, artists, and makers who contribute to its diverse artistic character. Due to the territory’s ongoing political uncertainty, these geographical and cultural divides have encouraged designers to investigate their own sense of identity, place, and what it means to be a “Palestinian designer” – or, as discussed by curator Dima Srouji, perhaps simply “a designer” in the world, as these place-specific labels become less important. In any case, designers in the diaspora are able to support and continue the use of traditional Palestinian craftsmanship – for example, glassblowing, ceramics, and embroidery, among many others – as well as incorporate alternative materials, lived experiences, and approaches in their design practices.

Through his multi-disciplinary practice, Dubai-based designer Faissal El-Malak brings attention to traditional techniques, forms, and motifs commonly used in textile to ceramic. Growing up between Montreal, Canada and Doha, Qatar, the Palestinian designer has cultivated a diverse, multicultural view of art and design, a notion which has influenced his own artistic practice. After studying fashion design at Atelier Chardon Savard in Paris, he launched his eponymous label in 2011. His attention to craftsmanship, interest in continuing traditional artisanal practices, and desire to tell a story through his designs is reflected in his garments as well as his latest design project.

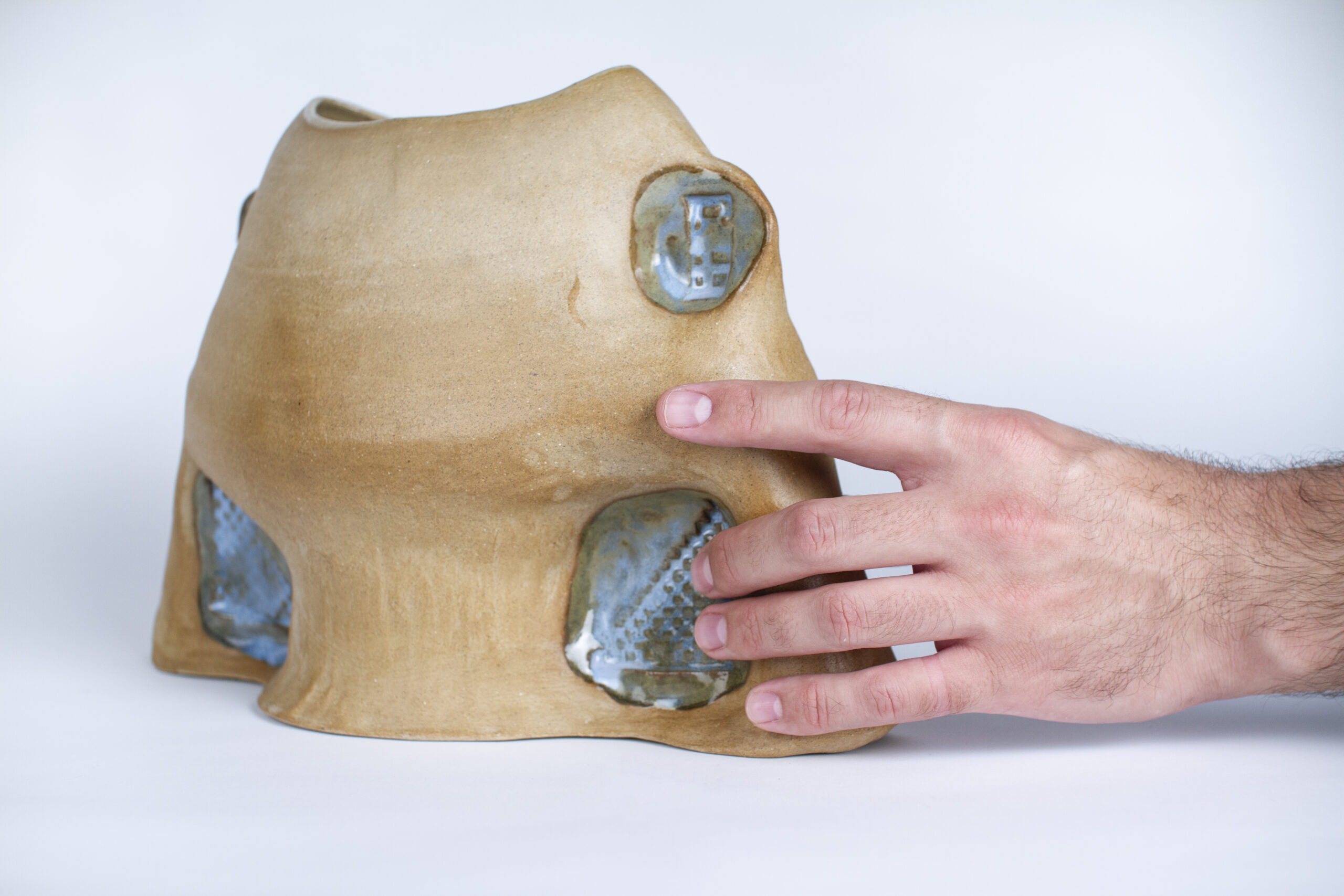

Most recently, El-Malak has shifted his interests to ceramic design, developing a collection with Palestinian artisans inspired by traditional Palestinian embroidery, both visually and technically. These unique pieces bring attention to the hand of the maker, bringing clay together in a way which emphasises the delicate yet tactile nature of both embroidery and ceramic. Symbolic motifs become visually-captivating sutures, drawing attention to the overall form of each piece. Through both of his practices, El-Malak has been able to support and explore age-old approaches to craft, incorporating and re-imagining them for contemporary audiences.

Ceramic design is a relatively new venture for you, how would you describe your current practice and approach to design?

I think that my approach makes sense when I put it in context to my own journey. Since relocating to Dubai in 2014, I have become immersed in a creative scene that went beyond the world of fashion I was accustomed to and exposed me to design and fine art. This happened through my personal curiosity and thanks to my studio space at Tashkeel, a shared art and design space in Dubai, where I began to approach my thinking in an interdisciplinary way through discussions with other members about their individual practices and through various educational programmes organised by the institution.

A pivotal moment for me was my participation in a programme organised by the British Council and hosted by the Victoria & Albert Museum in London where thirteen Gulf-based designers were invited to learn more about the design scene in the UK and one another’s practices; most designers in that course embodied the very multidisciplinary approach that I had been pursuing. This propelled me to reassess my own practice as a fashion designer where I had been feeling increasingly detached from fashion as an industry and more inclined to explore the essence of creativity. This led the debut of a new work utilising the mediums of ceramics, textile, and cement in the form of an installation at Amman Design Week in October 2019, curated by Noura Al Sayegh. Later that year, I won the Sabeel 2020 Open Call to design the drinking fountains for the Expo 2020 Dubai site in collaboration with jewellery designer Alia Bin Omair.

Continuing this trajectory into design as a multidisciplinary art, I am currently a participant in the Salama bint Hamdan Emerging Artists Fellowship (SEAF), which brings faculty and mentorship from the Rhode Island School of Design that I hope will continue to challenge me to advance my practice and incorporate new mediums and conceptual thinking.

“[The British Council programme] propelled me to reassess my own practice as a fashion designer where I had been feeling increasingly detached from fashion as an industry and more inclined to explore the essence of creativity.”

Bottom, L-R: “Corniche” Vase, “Spool” Vase, & “Bird” Jug, images courtesy of Amman Design Week

With regard to your background in fashion design, are there aspects of that experience that have found their way into your current design practice? If so, how?

I believe that fashion will always be there – it’s my foundation. I always imagine my work as the embodiment of an idea and an emotion – where a person is central to what I am creating, even if on a more subconscious level. The dialogue between three-dimensionality and two-dimensionality emulates the process of designing a garment while considering its construction, where something flat takes form to embrace the curvatures of the body. The symbolism of motifs is also central to my practice – particularly in the pieces presented here on Adorno.

Which three words would you use to describe the contemporary Palestinian design scene?

I think distilling an entire scene down to just three words is a difficult task – but I’m up for the challenge.

- Evolving: The scene is evolving from tradition and reinterpreting it into a current and fresh approach, while still honouring its roots. The Palestinian scene is definitely looking to the future.

- Craft: There is a groundedness to craft, because it is the basis of technique, concept, and form. It’s where we derive inspiration from.

- Playful: That which is Palestinian is often viewed through a historical lens, but there is a celebratory side where the rituals that embrace dance, music, and whimsical crafts are able to come through via contemporary design. This has always existed, but we have the opportunity to embrace this further through our collective practice.

“I always imagine my work as the embodiment of an idea and an emotion – where a person is central to what I am creating, even if on a more subconscious level.”

Top: El-Malak in his studio (Studio photos courtesy of Tashkeel, photography by John Marsland) // Bottom: “Bird” Jug

Working from the diasporic community in Dubai, in what ways are you able to create and/or connect to Palestinian identity and heritage through your work?

As a member of the Palestinian diaspora, my first tangible memory of my culture was through craft and traditional textiles that commonly surrounded me in the home where I grew up. This swayed my exploration of my heritage and my research [of] traditional materials, techniques, and motifs. This was first achieved through the numerous reference books about Palestinian embroidery and tradition. I [have] also had the privilege to be able to visit Palestine twice and to witness artisans working first-hand on these crafts. From there, I met with associations and craftspeople and, most importantly, connected to designers like me who are working toward similar ambitions of creating a contemporary language. I am not interested in creating a pastiche of these traditions, but, rather, in seeing how that essence can be transformed into a current design.

In reference to the “Bird” Jug, “Spool” Vase, and “Corniche” Vase, can you describe how you have interwoven traditional Palestinian forms and techniques into these very much contemporary pieces?

This project started with my desire to include Palestinian motifs in my fashion pieces around the time when I met the people behind Studio Kawakeb, a visual arts studio based in Beirut. I really connected with their playful approach to design and saw them as the perfect fit to commission them to design a series of Palestinian-inspired motifs. I was then inspired by the more functional aspect of embroidery on the traditional woman’s dress where, in addition to its narrative, decorative, and talismanic qualities, it also provides structural qualities to add reinforcement where needed, patching two panels together or mending areas of the dress. This inspired me to think about other materials that possess this ability to be patched together and, naturally, clay came to mind.

I had played around with clay slabs and manipulated them in a way I would fabric and imagined the motifs applied to these “embroidered” areas where the two layers of clay are sutured together. As with a garment, these stitches would shape the final outcome. If you look closely at these pieces, the final shape is what exists in the negative space outside the motif. This negative space is in itself inspired by historical vessels from archaeological sites around Palestine.

Conceptually, these pieces represent the notion of colourful, traditional craft acting as the very pillar that shapes the space and buttresses it to be a functional vessel. Together, these elements form a symbiotic balance between aesthetics and functionality. This, perhaps, sums up my approach to personal identity and practice.

Bio

Faissal El-Malak is a Palestinian designer who was brought up between Montreal, Canada and Doha, Qatar. He trained as a fashion designer in Paris’ Atelier Chardon Savard and recently moved back to the Gulf, finally settling in Dubai in September 2014. El-Malak has been working on developing his contemporary Middle Eastern design identity by bridging traditional artisan work with modern design.

Responses